Walkabout: Hot Fun in the Summertime -- Almost!

It’s not summer YET, we’re still waiting for spring to really kick in, but the weather has a habit of going from mellow to molten in no time at all in the city. With that in mind, and because I’m traveling today, to do my lecture tonight, I’m re-posting this timely article about cooling off,…

It’s not summer YET, we’re still waiting for spring to really kick in, but the weather has a habit of going from mellow to molten in no time at all in the city. With that in mind, and because I’m traveling today, to do my lecture tonight, I’m re-posting this timely article about cooling off, Victorian style. Much of what they did then, we could still be doing today, saving us money while doing our bit for the environment. Read on…

Let me just start by stating the unthinkable. I don’t have air conditioning. Now I am not opposed to A/C. I think it is invaluable in the workplace, in public gathering places, restaurants, stores, the subway, and in cars, but I never wanted it in my house. I have ceiling fans. Which brings up the point of this piece. What did the Victorians who built most of our houses do in the summer to keep cool? They had it much worse than we, in the first place.

Middle and upper class women were expected to wear constricting, tight clothes, with long sleeves, high and tight collars, multiple petticoats and undergarments, stockings, and heavy, tight whalebone corsets, from dawn to dusk. If they went outside, even more layers were added. Men of the same social classes had fewer layers, but were expected to be in long sleeved shirts, stiff starched collars, ties, and wool pants, waistcoats and suit coats. The lower classes may not have been expected to dress up, but societal decorum for them as well demanded the same amount of coverage of arms, legs and bodies. It’s a wonder they all didn’t succumb to heat prostration. New York summers haven’t changed in the last two hundred years. We have always had hot, sticky summers.

Part of the answer to summer survival lies in the architecture itself. Our row houses were designed to allow cooling cross breezes to flow through the house. When pocket doors are opened wide, air can pass through the house, and keep it cool and fresh. The thick party walls insulate the houses, keeping coolness inside for days. The Victorians knew that the relentless summer sun would eventually heat up the house, so they stopped in from getting in with a few simple, low tech, and still effective cooling techniques we should still use today.

First of all, direct sunlight is hot, so the front windows were outfitted with retractable wooden shutters, which, when extended, allowed the air from an open window to circulate, but kept out the hot rays of the sun. Shutters are used all over the world, especially in hot climates, for the same reason. We think of Victorian draperies to be dark, oppressive, overdone velvet shrouds, but summer draperies were not the same. Full length lace curtains replaced the heavy drapes in the summer, usually flanked by lighter weight solid curtains, much like today’s standard curtains. The lace curtains also reflected the sun light away from the interior, and gave the room a lightness that made it, if nothing else, psychologically more cooling.

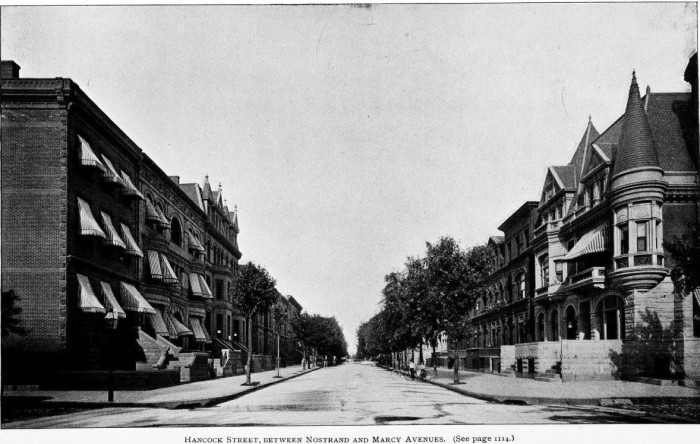

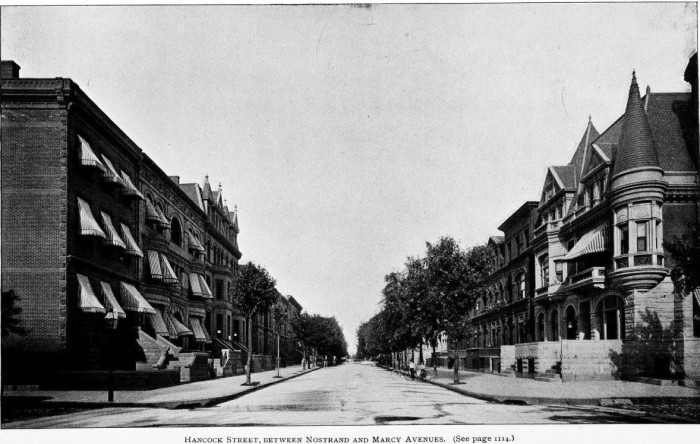

To further facilitate coolness, every house was outfitted with canvas awnings. Today, as we search for ways to use less energy, and depend less on expensive and energy draining air conditioning, we are realizing that those quaint, often striped awnings seen in photos of 19th century cities, had a purpose. Like many of our architectural practices, awnings have been in use since ancient Egypt, and the Romans used canvas awnings to shade their seats in amphitheaters and shade their merchandise in the marketplace.

After the Civil War, awnings became a part and parcel of American life. The advent of the steam engine made sails almost obsolete, and smart canvas and sail manufacturers soon turned to awnings to stay in business. It was they who came up with the stripes, colors and patterns that still are on the market today. The retractable frames, roll ups, and stationary awnings in both commercial and residential use can all be traced to their origin in seamanship and sails.

An awning shades the interior from direct sunlight, protects objects indoors from fading and UV damage, and can drop the temperature noticeably. It also allows a window to be open during inclement weather, which is often accompanied by cooling breezes. *Note for today’s home owners: According to the Department of Energy, awnings can reduce heat gain up to 65% in south facing windows and up to 77% on windows facing east. Awnings reduce stress on existing air conditioning systems, and make it possible to install new HVAC systems with smaller capacity, thus saving purchasing and operating costs. Air conditioners need to work less hard, less often. When used with air conditioners, awnings can lower the cost of cooling a building by up to 25 percent.

And then there is the ceiling fan. Human powered ceiling fans made of everything from feathers to rattan have been used by the Egyptians, to the British in India, to southern plantation owners. The first motorized ceiling fans were manufactured in the late 1860’s and 1870’s and ran on water power, not electricity. Turbines were used to turn a series of belts, which in turn rotated the blades. The first fans had only one long blade with paddles on both ends, much like an airplane propeller blade.

These early ceiling fans were used mostly by factories and later stores and restaurants, as many fans could be strung together by the belts. For the most part, these fans were very expensive and not practical for an average home as the large turbine engines needed a water source to power the engines. In 1882 Phillip Diehl invented a fan motor for the electric fan, modifying a sewing machine motor, but still very similar to what exists today. The motor enabled each fan to be powered separately, freeing it from the connecting belts. Diehl would go on to invent the “Diehl Electrolier,” which added a light fixture to the ceiling fan.

Hunter was an early pioneer of ceiling fans, as well. Hunter Fan and Ventilating was started by two Irish immigrants, father and son, John and James Hunter, in Syracuse, NY in 1886. They started out making water meters and turbine driven water powered fans for industry. In 1889 they moved their plant to Fulton, N.Y., where they concentrated solely on producing ceiling fans using an electric motor they devised, independent of Diehl. They were known for their high quality product, and some of their early fans, both belt driven and electric have been restored for use today. They are now the largest fan company in the world, known now as Hunter Douglas. Emerson Fans, started in 1895, featured the first fan to have a motor that ran on alternating current.

History credits one Schuyler Wheeler as the inventor of the electric table fan, in 1886. In 1900, on a hot summer day, Lionel Cowen invented his own electric fan, here in New York City, but gave it up when people lost interest as soon as the weather cooled. He turned his energies elsewhere, and went on to invent and produce Lionel Trains. All of these early fans, ceiling and table, were very expensive, and very few homeowners of the day could afford them.

As the 20th century progressed, practical air conditioning would be developed, and fans did not make a comeback in this country, at least in the Northeast, until the 1970’s when energy costs soared and alternatives to expensive A/C were once again explored. Today ceiling fans are at their peak of popularity again, and many of the old designs are again making a comeback.

As energy costs continue to climb, and summer energy use threatens to overload our systems, it’s time to once again emulate some of the innovations of the past. Shutters, awnings, curtains and ceiling fans can all reduce energy consumption, and save us money. Imagine our brownstone streets once again festooned with canvas awnings, stripes and solids, with pennons and scallops, catching the summer breeze.

Has anyone noticed that the photo at the top is mis-identified? That’s Hancock Street between Marcy and Tompkins for sure. Just look at all those Montrose Morris buildings…..