Walkabout: Kidnapping General Grant, Part 1

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this story. In American history classes we learned that Ulysses S. Grant was the brilliant commander of the Union Army during the Civil War. He was appointed by Abraham Lincoln, and opposed his fellow West Pointer, General Robert E. Lee, during the horrendous War Between the States, the…

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this story.

In American history classes we learned that Ulysses S. Grant was the brilliant commander of the Union Army during the Civil War. He was appointed by Abraham Lincoln, and opposed his fellow West Pointer, General Robert E. Lee, during the horrendous War Between the States, the war which changed the United States forever.

After the war, he was one of the most popular and well-known people in the country, up North, anyway. He would go on to win two terms as the eighteenth president of the United States. He was elected at 46, the youngest president of the country, at that time. He died in 1885, at the age of 63, a victim of throat cancer.

Some later historians regarded his presidency as pretty awful, due to the corruption of some of his key appointments, but he’s always been regarded with great pride and respect, especially in the years following his death.

Today, history is much kinder to Grant as president, giving him credit where credit is due. His efforts to pull the country back together again after the war and his genuine efforts to include African Americans as full participants in American society are now lauded.

Civil rights on a presidential level did not receive as much attention again until after World War II. Grant also presided over the country when technology and progress were making huge strides, helping to create a vital consumer middle class, and a changing America.

Before he died in New York City, in 1885, Grant expressed a desire to be buried in the city he had grown to love. After his death, the Union League Club, an influential Republican club founded by Manhattan’s elite, wanted to build a large memorial and mausoleum to house and honor him.

Riverside Drive was chosen, in part because his widow Julia lived near the site, and could easily visit him. A committee was set up, funds were raised, and long story short, the General Grant National Memorial, the official name of Grant’s Tomb, was dedicated in 1897. When Julia died in 1902, she was laid to rest beside him. The tomb became one of New York City’s most famous monuments.

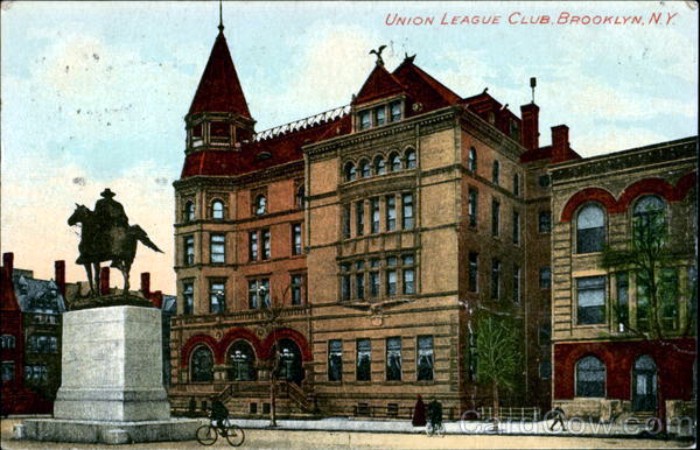

Here in Brooklyn, Grant was honored in a different way. Brooklyn’s own branch of the Union League Club, founded by the Brooklyn’s Republican movers and shakers, built a new headquarters in the Bedford section, one of Brooklyn’s most up and coming upscale neighborhoods.

They commissioned architect Peter Lauritzen to design a large clubhouse on the corner of Bedford Avenue at Dean Street. Lauritzen’s building was completed in 1890. Two of the most noticeable features of the façade are the very prominent terra cotta busts of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, placed just above the entrance. But that wasn’t enough of a tribute.

Soon after moving into their posh new clubhouse, the members began fund raising for a memorial to Grant to be erected across the street. The intersection of Rogers and Bedford Avenues at Dean Street, with Bergen Street at the rear, had resulted in a large triangular piece of land too small to build on, but perfect for a small park and a statue.

The Leaguers commissioned prominent sculptor William Ordway Partridge to create a heroic statue of General Grant which would commemorate the man, the victory of the Union, and his presidency.

Partridge was one of America’s finest sculptors, and many of his works are part of New York City’s landscape, including statues of Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Samuel Tilden and more.

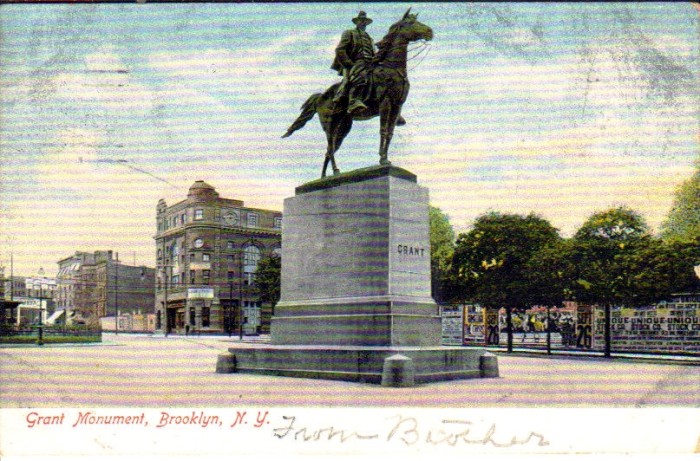

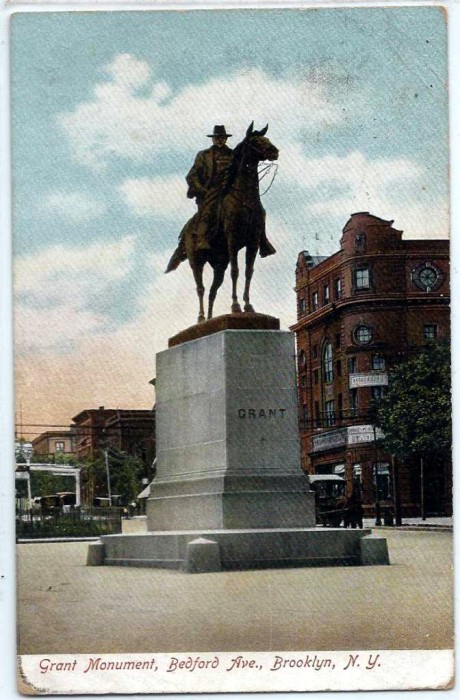

Here he came through with one of his finest works, a large equestrian statue of Grant that captures not only the heroic aspect of the General, but also the humanity of the man, depicted as a youngish, but battle-weary warrior resolutely facing the future.

The statue was placed on a large broad granite base and installed towards the point of the triangle, facing north. Grant faces the 23rd Regiment Armory, fittingly, and also has quite a view of Manhattan, the future of the city, as it were.

By the time the statue was dedicated, in 1896, plans for the unification of New York City were already in motion, plans backed by most of the members of the club, although ironically, they would mean the downfall of this particular branch of the Union League Club.

At any rate, the unveiling of the statue of General Grant was the occasion for much pomp and splendor. It also caused the renaming of the plaza to Grant Square, now a part of the new St. Marks District, one of Brooklyn’s wealthiest neighborhoods.

The statue was put into place in April of 1896, and a grand dedication ceremony was planned for April 25, 1896. It rained that day, but that didn’t stop thousands from gathering in front of the club.

Marching bands paraded by an assemblage of dignitaries, speeches were given, and at last, the young grandson of General Grant, also named Ulysses, pulled the cord that dropped the tarp around the statue, revealing it to the world.

Everyone loved the statue. It really is a beautiful work of art, and is one of Partridge’s finest works. His articulation of the horse’s musculature is incredible, and his depiction of General Grant shows a sympathetic rendering of the military hero, the president-in-waiting, and a man who would sacrifice himself to duty and country.

It’s also quite large. The little park around the statue was improved with a fountain and landscaping. The general soon became a familiar site to those travelling down Rogers and Bedford, both busy thoroughfares joining northern and southern Brooklyn.

In the next 20 years, after Grant began gazing towards Manhattan, much changed in the city. A year after the dedication of the statue, Grant’s Tomb was dedicated on Riverside Drive. Two years later, in 1898, Brooklyn went from being an independent city to becoming a borough.

Its mayor became a borough president. The area around Grant Square still grew in popularity. A large residential hotel called the Chatelaine was built in 1912, and soon after, the Loew’s Bedford Theater was built, both facing Grant’s statue.

The armory was busy hosting its elite regiment, but also hosted automobile shows, athletic events, and other social functions. The doctors were still across the street from the armory, and next door to the Union League Club, the Kings County Wheelmen, an upscale bicycle club, had their headquarters, and next door to them, fancy restaurants opened up onto the street.

There were stores and restaurants on Bedford, Rogers, Bergen and St. Marks. There were also churches, elegant row houses and large upscale apartment buildings.

By the 1920s, Bedford Avenue had become Brooklyn’s official Automobile Row. Although Grant’s Square stayed pretty much as it had been, the blocks of Bedford north and south of the square became home to automobile dealers, service centers, accessory shops, garages and other automobile related businesses.

Bedford Avenue became one of the busiest streets in Brooklyn. There were so many cars, that a traffic station had to be built high above the traffic, at the edge of the park where General Grant looked northward.

In 1912, the Union League Club had decided to move. They ended up merging with Manhattan’s club, and so sold their Bedford Avenue building to the Unity Club, a Jewish organization. This part of Bedford had a growing Jewish population that would get even larger in the 1930s.

They used the clubhouse for meetings and later, a yeshiva. The club took on the building, but by now, the statue and park were the responsibility of the city’s Parks Department. The Union League had donated the statue to the city years before.

More time went by, and by 1941, the nation was embroiled in World War II. The war effort had forced the country out of the Great Depression, but the nation was still in rough shape. One of the great programs to come out of that era was the Works Progress Administration, the WPA.

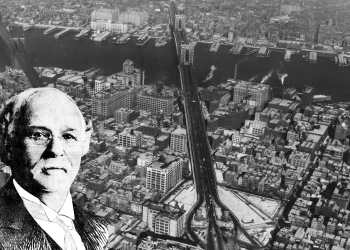

The head of the city’s Parks Department was Robert Moses, the powerful and controversial “Master Builder” of New York City. Using WPA funding, he was able to build new parks, pools, highways and more.

He also spent money refurbishing our older parks and monuments. One of those refurbishments was to Manhattan’s General Grant National Memorial.

Grant’s Tomb had been given a much needed facelift by Moses. It had been poorly maintained over the years, especially during the Depression, when private and public funds had dried up. Moses felt the General deserved better, as this was one of New York’s greatest public works.

He had a lot of work done on both the interior and exterior of the building, and the surrounding grounds, all designed to bring tourists and money back to the Tomb, and restore it to the pantheon of the city’s great attractions.

In the course of this rehabbing, Moses had been working with the Grant Monument Association, an advocacy group for the monument led by former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Herbert L. Satterlee. Satterlee was a Brooklynite, and in addition to leading the GMA, he also was head of several Brooklyn civic organizations.

The GMA, Moses and the Parks Department had thought it would look great for Grant’s Tomb to have a nice statue of the General in the plaza in front of his tomb. After looking around, they couldn’t find one for sale, and they had priced a new statue, and decided that a new sculpture would be too expensive.

But wait, Satterlee thought. There’s that big, beautiful statue of the general in Brooklyn! Let’s just take that one, and put it in front of Grant’s Tomb. Satterlee got the Municipal Art Commission to back him, and Robert Moses placed a formal request that Brooklyn give their General Grant Statue to Manhattan to place at Grant’s Tomb.

Everyone in favor of the idea thought it was a done deal. Moses told the newspapers that after the statue was moved, they would put a plaque on the base telling the world that Brooklyn had generously donated the statue to the Monument.

All that needed to be done was to get the moving men ready and General Grant was going to ride in glory to his new home on Riverside Drive.

They really didn’t know Brooklyn and its people very well.

Next time: The fight to keep General Grant in Brooklyn, and more.

(1912 postcard)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment