Walkabout: The “Bain” of Her Mother’s Existence, Part 2

In Part 1 of our story, we met Louise Bain, who was disinherited by her wealthy Park Slope mother, Martha Brasher. In this installment, which takes place in 1920, the daughter tries to overturn her mother’s will. Next, read Part 3. Mrs. Bain sued, trying to break the will. She and her attorneys argued that her mother was not…

In Part 1 of our story, we met Louise Bain, who was disinherited by her wealthy Park Slope mother, Martha Brasher. In this installment, which takes place in 1920, the daughter tries to overturn her mother’s will. Next, read Part 3.

Mrs. Bain sued, trying to break the will. She and her attorneys argued that her mother was not in her right mind when she cut her out of the will. They also argued that Mrs. Brasher’s lawyers had too much influence, as they were executors and beneficiaries.

The Church Charity Fund, which received half the estate, teamed up with the lawyers for the executors to prove Martha Brasher sane, Louise Bain a horrible daughter, and the will valid.

All sides put forth a good case for their points. The trial lasted a week before the jury received the case. After long deliberation, they returned with a verdict upholding the will. Mrs. Bain lost. Then the story takes a strange turn.

In the aftermath of the verdict, some details began to come out. It turns out that most of the jurors wanted to give Mrs. Bain something out of the will. They searched through every page of the will and the four codicils looking for a way. Then they thought they saw one. Buried in the complicated will was a trust fund of $50,000 for Mrs. Bain. The jurors were set to give her that amount, plus another $10,000 in attorney’s fees.

Feeling good about that, they upheld the rest of the will, saying that Mrs. Brasher, as cruel and unreasonable as she may have been, had the right to do with her money as she pleased. But then someone found out something that killed the deal. Buried in one of the codicils was a stipulation that if Mrs. Bain contested the will, the bequest of $50,000 was null and void. How no one on either side saw either of these items before the case even went to trial is rather puzzling. The jury had to come back and announce that the will would stand. Mrs. Bain was out of luck.

Of course, she and her attorneys appealed. During the period before the trial went to the Appellate, more details of the family dynamic appeared in the papers. It’s not clear if this appeared in the testimony, or was from interviews. It seems that Louise Bain’s parents, both of them, had been less than stellar.

When Louise married her first husband, Captain Clayton, the parents had been thrilled. But he was stationed at West Point, and he and Louise lived on base. The Brashers wanted them closer, so Mr. Brasher promised Captain Clayton that if he resigned his commission, he could become a partner in Brasher’s very lucrative Brooklyn oilcloth company.

Clayton resigned his commission, something he had worked very hard to get, and came home. He began to work for his father-in-law. Brasher decided to retire, and instead of handing even a part of the company to his son-in-law, as promised, sold it instead. Captain Clayton was furious at this breach of trust. He ran for State Congress, won, and began spending his time away from home.

Louise and her son William were in Brooklyn, where her father had been giving her a generous allowance, even after the marriage. When the rift between her husband and her father occurred, she sided with her husband. The allowance stopped. In 1912, William Brasher died.

In spite of his wife’s loyalty, Captain Clayton never forgave her parents, and the marriage failed. In the meantime, she had met George Bain. When her husband divorced her, she married Bain. She quickly became pregnant, and they had a child, Jeanette.

But the Bain marriage also had its problems, and mother and daughter grew more estranged. It didn’t help that George Bain had taken to sending numerous postcards to the Brasher household, accusing Mrs. Brasher’s family of being crooks and thieves.

Martha Brasher was a Gerritsen, a descendent of one of Brooklyn’s oldest Dutch families. Gerritsen Beach and other Flatlands sites are named after them. Mrs. Brasher was very proud of her lineage. George Bain kept sending postcards to the Park Slope house with cryptic messages. “Were the Gerritsen’s smugglers or pirates?” “Is it true Old Man Gerritsen drove the first car down Flatbush Avenue?” That was it for Mrs. Brasher, all contact was cut off.

When little Jeanette Bain was nine years old, she sent a touching Christmas card to the grandmother she had never met. It read, “Dear Grandmother, although I have never seen you, I wish you a merry Christmas. We had a fire in our house today, but my dollies and toys were saved. Jeanette.”

That note might have moved stone, but not Martha Brasher. A few days later, Mrs. Bain received a registered letter from the law firm of Doughty & Smith. It contained the postcard from Jeanette and a letter from the firm warning Mrs. Bain to not communicate, or allow her daughter to communicate with Mrs. Brasher under any circumstances. This was the same law firm that would be the executors of the Brasher estate. Under the terms of the will, they were set to receive over $400,000 for their services.

Newspapers in Brooklyn and across the state were carrying this story. Everyone wanted to read about the disinherited daughter and her grandchild. The fact that the bulk of the fortune was going primarily to a charity that the mother had never had any prior dealings with and a law firm was especially appealing to readers.

Mrs. Bain’s attorneys, Frank A. Crowe and Edward J. Connolly, filed their appeal. They questioned the sanity of one of the defendant’s witnesses, the truthfulness of another, as well as the motives of the executors. The judge in the case had ruled that the lawyers had not exerted undue influence on Mrs. Brasher, even though they stood to get their hands on a great deal of money.

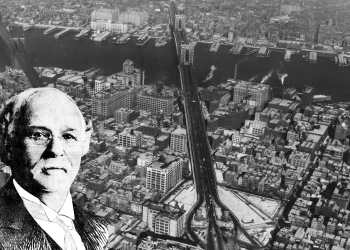

By the end of 1920, the legal bills were mounting, and Louise Bain was still working in a Fulton Street shop. The family had moved from their comfortable rooms at the St. George Hotel, and was now living in a flat in a row house on Henry Street. Jeanette Bain, who was now 16 years old, was also working.

George Bain was not mentioned. Captain Clayton had been killed in World War I, and their son William was married and living elsewhere. The Bain family, as well as the rest of Brooklyn, was now waiting on the Appellate.

Next time: the conclusion of the story, including more surprising twists. For more family background, and the details of the trial, please see Part One of this story.

(Top photo: 119 Henry Street, the Bain home during the trial. Photo by Scott Bintner for PropertyShark)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment