Walkabout: “The Landlord of East New York,” Part 1

Edward F. Linton was an East New Yorker who was instrumental in turning much of the old town of New Lots into one of late 19th century Brooklyn’s nicest neighborhoods.

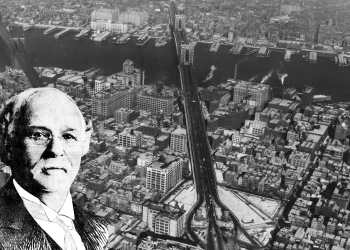

Photo: Brooklyn Public Library

Read Part 2 of this story.

East New York. For many who read these pages, or live in more affluent parts of Brooklyn, the neighborhood of East New York is terra incognita, the land not explored, or rather, the neighborhood passed through as fast as possible in the cab to the airport; that vast stretch of Atlantic Avenue between Bedford Stuyvesant, Crown Heights and the Conduit. If you take the subway a lot, you may have changed trains at the massive hub now called “Broadway Junction,” one of the few stations where three different lines of trains cross over each other, with the LIRR station not too far away, as well.

From the elevated station, one can see across to Jamaica Bay and Kennedy Airport. In the other direction, you can see the Victorian-era cottages and homes that make up the neighborhoods of Cypress Hills and Highland Park. You may even be able to catch a glimpse of Highland Park itself, one of Brooklyn’s larger neighborhood parks. What you may not realize is that practically everything I’ve mentioned was influenced in some way by a man named Edward F. Linton, an East New Yorker who was instrumental in turning much of the old town of New Lots into one of late 19th century Brooklyn’s nicest neighborhoods. This is his story.

Edward Linton was born in Baltimore in 1843, but grew up in the Weymouth, Massachusetts area. When the Civil War rolled around, he enlisted with the Mass. Volunteers and went to war. He apparently didn’t talk about it much, so there aren’t a lot of details emerging from his war service. After the war, he and his wife Julia made their way to New York, where Edward went into the fireworks business. More than likely, he learned explosives during the war.

By 1877, he was the president of the Unexcelled Fire-works Company of New York. That year, and the year after, he penned letters to the editor of the New York Times explaining the difference between fireworks (good) and firecrackers (bad) to the uninitiated. He wrote at great length about how fireworks were now safer than ever, and fears of burning down the city were exaggerated. After all, a cow had burned down Chicago, not fireworks. He likened the banning of fireworks from Fourth of July celebrations, such as happened in Baltimore, to be a sin, and invited anyone who wanted to see the precautions taken by his company to insure safety, to come down to his Chambers Street warehouse and see for themselves. He would also hand out copies of the city statutes on fireworks.

Fireworks were a good metaphor for this man who listed his profession in the 1880 census as “pyrotechnician.” Edward Linton was a go-getter, and a persuasive salesman. But later that same year, there was a spectacular fire in the New Lots factory of Unexcelled Fire-works, and Linton was severely burned in it. Most of the building was lost, and Linton had to take time to heal. He was expected to be up and running in a few weeks, but when he came back, he changed professions, and decided to go into real estate, an industry with just as much potential explosive power, but less heat.

He and his family were living in the town of New Lots. Originally part of Flatbush, the New Lots area had been settled by Dutch farmers who couldn’t find room to farm in Flatbush, and came over there, in the 1700s, to settle the new lots, hence the name. The names of some of these New Lots farmers are still familiar to us, as they became names of streets and roads: Van Siclen, Schenck, Vanderveer, Wyckoff, Duryea and Van Wycklen. In 1852, New Lots seceded from Flatbush, and became an independent town.

As the 19th century progressed, these Dutch “Knickerbockers” as they were called by the papers, began selling off their farmland to developers.By this time the sellers were the grandchildren of the families that had worked so hard to get their land. Between 1855 and 1867, a developer named Charles Miller had built over 600 houses, all of which helped make quite a tidy little town by the time the Linton’s got there. Edward Linton began his empire by buying a house. In 1882 he purchased the old Andrew Wagner home, which had been empty for some years. The address for that home was not mentioned in the article. The papers did say that he planned on a total renovation and modernization of the home. He was just getting started.

He followed that up by buying the much larger Stoothoff farm, a $100K purchase that netted him the farmhouse, and land that he divided up into 600 lots, all near the last stop of the trolley line. He immediately began selling off lots, with restrictions on what kind of houses could be built, and soon moderately upscale suburban houses began to rise on the properties. When he had bought the farm from William Stoothoff, people called it an expensive folly, but in two years, he still had most of the land, and had already made a $50K profit. They stopped laughing.

Linton was not the only developer and speculator to buy up the old farmland, there were others who put their substantial mark on New Lots. But Linton soon became the largest of them. The Stoothoff farm was followed by the Schenck farm, the Wyckoff and the Lennington farms. By 1890, Edward Linton literally owned half of East New York. Beginning with Charles Miller, the area’s developers, including Linton, had advocated for improvements to the infrastructure of the town, such as sewers, paved roads and sidewalks. They also wanted improved public transportation. In order to get this, it was necessary for the town of New Lots to become a part of the City of Brooklyn, so in 1886, New Lots officially did so, and became known as East New York, the new 26th Ward of Brooklyn.

Edward Linton had already been crowned one of New Lot’s movers and shakers. Like many important men, he thought the next move was naturally in politics, and in 1879, he formed a club from which to launch his campaigns. His first office would be in the State Assembly, he thought, and he ran as a Republican for that office. He lost in the primaries. Undaunted, he began to consolidate his base, and he was one of the founders, as well as the first president, of the Board of Trade of the Town of New Lots, which was established in 1884.

He became a firebrand in local Republican politics, and was written up often in the Eagle and other Brooklyn papers for his stand on any number of issues, and also for being rather contentious and difficult at times. In 1884, he got into a fight with local Republican leaders, and they all carried huge grudges for over a year, so much so that in 1885, they finally asked Linton to resign from his leadership roles in the local party. It took him another six months to tell them he was not leaving, and in 1886, would continue to be a member in good standing. He wouldn’t go away. Eventually, they all made up, but even though he later ran again, this time for the Senate, Linton was never elected to public office.

But hey, who cares? Because there was so much going on, Edward Linton wouldn’t have had time to go to Congress, anyway. He established his business office on the corner of Atlantic and Van Siclen Avenues and as the largest property owner and landlord on Atlantic Avenue was elected president of the Atlantic Avenue Improvement Commission. In 1890, he was appointed by Brooklyn Mayor Chapin to the join a prestigious commission to study a consolidation plan that would join Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Bronx, Staten Island and Queens into a Greater New York City. He was for the consolidation. Others were not. There would be conflict.

Edward Linton had a lot of interests, and had his fingers in a lot of pies. He was interested in just about everything that went on in the 26th Ward. One of his favorite interests was the new and very popular game of baseball. Professional leagues were just beginning to form, and teams in Brooklyn were playing each other, as well as teams from other cities. It was a very exciting time for the young sport, and Linton wanted to be a part of it. He became one of the Directors of the Brooklyn League Baseball Clubs, an affiliation of some of the city’s own teams, of which there were quite a few. Wouldn’t you know it? Even baseball got him in trouble, and landed him in court, and in the papers.

Baseball, politics, commissions, railroad lines and sewers: All would be bones of contention in Edward Linton’s life. It’s not easy being the “Landlord of East New York.” Please catch more of the story in our next chapter. Mr. Linton was just getting started.

(Photo: View of East New York – Brooklyn Public Library)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment