Walkabout: The Rescue of Charles Nalle -- A Troy Story, Part 3

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story. Charles Nalle, his body battered and bleeding, blood streaming from his wrists where the heavy slave manacles bit into his skin, stumbled up the embankment of the Hudson River, into the town of West Troy, N.Y. It was April 27, 1860, and Nalle had just escaped…

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story.

Charles Nalle, his body battered and bleeding, blood streaming from his wrists where the heavy slave manacles bit into his skin, stumbled up the embankment of the Hudson River, into the town of West Troy, N.Y. It was April 27, 1860, and Nalle had just escaped being taken back into slavery.

He was, according to the law, still the property of his half-brother Blucher Hansbrough, of Culpeper, Va. That morning, he had left his employer Uri Gilbert’s house on 2nd Street, in Troy, and walked to the bakery, intent on getting bread for his employer’s household.

Two years had passed since that fateful day in 1858 when he had boarded a boat in Washington, D.C., on his way to freedom in Philadelphia, and then on to upstate New York, bound for Canada.

To look at the man making his way up the embankment, one would scarcely have taken him to be the average Negro slave. He looked as Caucasian as any other free white man. He was the son of a Virginia planter named Peter Hansbrough and his slave named Lucy, who was herself half white.

Charles was four years older than his half-brother Blucher, and was given to him by their father. The two men looked so much alike, a change of clothing would have obscured master from slave.

But blood made all the difference, and Charles’ African lineage had assured him of a life of slavery. Unless he took his fate in his hands, and boarded the Underground Railroad to freedom.

The story of Charles Nalle’s early life, his family in Virginia and Washington, and his life in Troy up until this day can be found in Part One and Part Two of this story. We ended the last chapter with Charles Nalle escaping his captors and jumping on the ferry to West Troy, which today is the city of Watervliet.

The hounds of hell were behind him, but so was salvation, in the person of Harriet Tubman, the “Moses” of the Underground Railroad, a woman who had never lost a passenger. And she, and the members of the Vigilance Committee, and the citizens of Troy, weren’t going to start losing one now.

The authorities in Troy had telegraphed ahead of Charles Nalle, so as he pulled himself up the west bank of the Hudson, and began running along Broadway, the police were waiting for him. Exhausted, beat up and drained of adrenaline, he was taken away without much resistance.

The West Troy authorities took him to a brick building near the ferry dock, to a judge’s office on the third floor, awaiting the arrival of Troy’s Marshall and his deputies. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Nalle, a second rescue was about to take place.

Earlier that day, while Nalle had been kept prisoner in the U.S. Commissioner’s office in downtown Troy, his landlord, William Henry, had stood before the crowd and made an impassioned speech about freedom and a man’s right to self-ownership.

He told them how Nalle had been brought before the Commissioner shackled as a prisoner whose only crime had been in stealing his own body.

He said that Nalle had been condemned to be taken away from his home, his friends and his employer in Troy to be again imprisoned on a cruel southern plantation where he would no doubt be tortured and killed for the crime of wanting to be free.

Could the people of Troy, he asked, permit this good and intelligent man to be so deprived of liberty, a liberty they so freely had in abundance? Would they let a bounty hunter, a despised slave-catcher who trafficked in human misery, and his employer, a slaveholder from Virginia, win the day?

Would they allow Charles Nalle, a man many of them knew and liked, to be dragged back into slavery? The good people of Troy roared “No!”

So as Charles Nalle was taken out of the building, they had pressed forward, and fights broke out. The rescue had begun. In the melee, Harriet Tubman, disguised as an old and frail woman, had pulled Nalle out of the crowd and down towards the river.

She meant to guide him further, but she and her people were separated from him, leaving him to cross alone. As Nalle was being locked away in West Troy, a ferryboat carrying Harriet and three hundred other people was only ten minutes behind him. Harriet and the others ran from the ferry up the river bank, but Charles Nalle was gone.

A group of children playing by the river pointed the way, “He’s in that building,” they said, pointing to the brick building by the docks, “Up on the third floor!”

The crowd composed of blacks and whites, men and women, surged ahead, approaching the panicking officers of the West Troy constabulary. They rushed up the stairs, and the West Troy police began firing into the crowd, hitting two men, who fell backwards on the stairs, injured but not dead. The crowd kept coming.

The police were outnumbered, and in the chaos Harriet Tubman and her men rushed into the room and took the exhausted and bleeding Charles Nalle down the stairs. According to legend, the five-foot Harriet Tubman, herself battered from the assault in Troy, took Charles Nalle in her arms, and like a mother with her child, carried him down the stairs.

When they reached the street, a stranger rode by on a wagon. He stopped and asked what the commotion was. When he heard the story, he jumped down from the wagon and offered it to the rescuers.

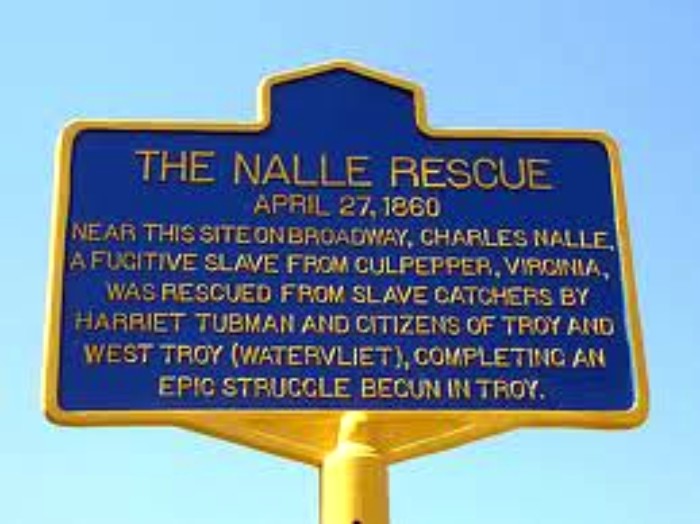

“This is a blood horse,” he exclaimed, “Drive him till he drops!” Today, a commemorative marker, erected in 2009, notes the place where the second rescue took place.

Harriet, along with a small number of supporters and at least one of Charles’ friends, jumped in the wagon, and headed west on the Shaker Road, towards Schenectady and the Erie Canal.

They stopped in Niskayuna, just outside of Schenectady, where Charles’ chains were struck from his wrists, and the bruised and battered man was hidden until he was recovered enough to keep going.

He moved northwest to Amsterdam, and stayed in hiding for several months. Meanwhile, his employer, Uri Gilbert, and his friends raised $650 to purchase his freedom from Blucher Hansbrough.

Charles Nalle came back to Troy a free man and a hero. He was able to contact his wife, Kitty, and three months later, she and their five children joined him in Troy, where they lived through the Civil War years. Charles learned to read and write.

They had three more children, and stayed in Troy until 1867. The family moved back to Washington, to be near relatives on both sides.

There, Charles was employed by the Post Office. He died in 1875, and is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery. Many of his descendants still live in the D.C. area. He never told any of his children about his life before his freedom, or the rescue in Troy.

So what happened to the rest of our players in this story? Charles Nalle’s half-brother Blucher Hansbrough had always been a rake and a spendthrift. Before Charles’ escape, he was best known for gambling, drinking and womanizing.

He liked racing horses, dog and cock fighting and cards. Most of the slaves on his plantation lived in fear that he would sell them at any time, in order to pay off his many debts. He fathered many children on several of his female slaves, no doubt to the horror of his wife, who of course, never said anything.

After going back to Virginia after his close escape in Troy, the Civil War changed the course of his life forever. During the winter of ’63 to ‘64, over 20,000 Union troops from the Second Corp of the Army of the Potomac camped on his land.

They took over his house as headquarters, and marched from there to the Battle of the Wilderness. Long afterward, in 1873, Blucher Hansbrough died. He did not leave a valid will.

Horatio Averill, the man who betrayed Charles Nalle, barely got out of Troy alive. The crowd was ready to inflict great bodily harm upon him, but he managed to get into a coach and get out of the city. He was never welcomed in Troy again.

He later claimed that he had not betrayed Charles Nalle, and offered up several other names as the likely betrayers. The Troy papers did not buy it, and for many months later, were still printing accusations and letters from irate readers.

In 1875, after the announcement of Charles Nalle’s death, those accusations came back to haunt him once again.

By that time, he had moved on to the coal business in West Virginia with his brother. They made a fortune. He sold his interests, moved to New York City and managed to reinvent himself, becoming a State Supreme Court judge.

He returned often to his hometown of Sand Lake, in Rensselaer County, where he had first met Charles Nalle, and gained his confidence, those long years ago. He and his brothers built a resort hotel and community nearby, and today, the town of Averill Park bears their name.

He died in 1887, but before he left this earth, the Averill Park development was foreclosed on. He died leaving his brother and sister-in-law with the mess.

Uri Gilbert continued his great success in the carriage and coach business. His company made railroad cars and the omnibus trolley cars used in New York, Boston, and other cities. He became mayor of Troy between 1865 and 1870. He was known in Troy as a great philanthropist as well as an important businessman.

He was on the boards of the orphan asylum, hospitals, banks and educational institutions. He died in 1888 at the age of 79. His house at 189 2nd Street still stands and is part of the Washington Park Historic District.

Several people from Troy were charged for some of the actions that took place on April 27, 1860. They were all acquitted, and no one was happier about that than the prosecutors, the sheriff, his deputies and all officials associated with the case.

The Troy paper noted that “this, we hope, is the last of the series of prosecutions in respect to the rescue. So far, they have proven a farce, and it is likely they will do so to the end of the catalogue if they are continued. We have information, which we believe is based on reliable authority that henceforth they are to cease.”

Harriet Tubman, of course, was one of the greatest heroes of the 19th century. She personally led over 300 people out of slavery into freedom, including most of her family.

She later told audiences, “I was conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can’t say – I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

During the Civil War, her uncanny ability to slip past the authorities made her a valuable scout, and she became the first woman to lead an assault during that war. When she wasn’t scouting, she was a nurse and a cook for the Union Army.

In spite of her service to the Union, she was denied pay and recognition by the Army until 1899. She joined the women’s suffrage movement, and worked alongside Susan B. Anthony and others. In spite of her growing fame as she grew older, she lived most of her life in dire poverty.

Her farm in Auburn was paid for by friends, and she often had so little money that she was forced to sell her livestock in order to buy train tickets to her many speaking engagements.

By the early 20th century, she was sick, still suffering from the headaches that plagued her entire life, caused by a blow to the head as a child, while still in slavery.

She died of pneumonia in 1911, and was buried with full military honors. Today Harriet Tubman is one of the most famous and admired women in American history.

One of Charles and Kitty Nalle’s sons, John, grew up in Washington, and became a prominent educator, and eventually, the Superintendent of Schools for that city. An elementary school today bears his name. After his retirement in 1932, the 72-year-old Nalle stopped in Troy on his way to a vacation in Saratoga Springs.

Here he was greeted as a local celebrity. He had only been four, and living in Washington when the great rescue took place. Of his parent’s eight children, he and one other sibling were the only ones still living. His father had never told them the story of his rescue, and he heard of it standing in front of the building where the event took place.

The people of Troy had placed a memorial plaque on the old City Bank Building in 1908, celebrating the rescue as one of the ten most defining moments in Troy’s history.

Standing in front of the monument in 1932, John Nalle listened as an aging Garnet Douglass Baltimore, the first African American engineer to graduate from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and the architect of Troy’s own Prospect Park, told John Nalle the story of his father’s escape. Mr. Baltimore’s own father had been one of the rescuers.

The papers eagerly covered the story. Nalle was fascinated by his father’s story, and planned to write a book, but died of a heart attack soon afterward.

A year later, the Sons of the Revolution, a civic group, replaced the plaque with the bronze marker which still marks the place where Troy’s people decided that a man’s freedom was more important than the letter of the law. That marker was again restored in 1987.

It reads, “Here was begun on April 27, 1860, the Rescue of Charles Nalle, an escaped slave who had been arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act.”

Once again, I must recommend Scott Christianson’s book, “Freeing Charles: The Struggle to Free a Slave on the Eve of the Civil War.” My other sources were the Troy Times, the Auburn Citizen, and general research on the lives of Harriet Tubman, Horatio Averill and Uri Gilbert, among others.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment