Food for Brooklyn: The Story of the Great Wallabout Market

Throughout Brooklyn’s history, a lot of things have come and gone, but one of the greatest losses has to be the Wallabout Market in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

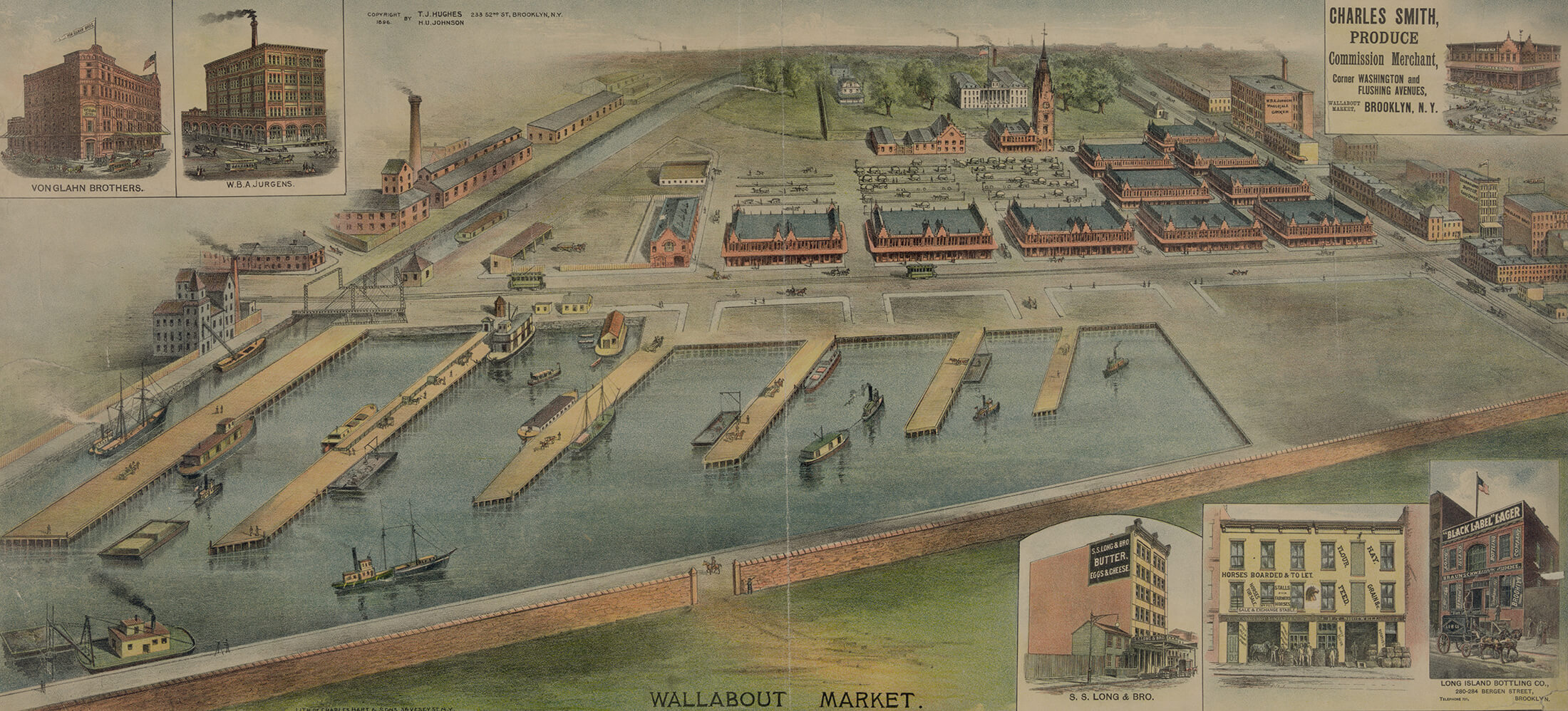

Detail from a print of Wallabout Market circa 1896. Image via the Library of Congress

Editor’s note: This story originally ran in 2014 and has been updated. You can read the previous post here.

Throughout Brooklyn’s history, a lot of things have come and gone, but one of the greatest losses has to be the Wallabout Market in the Brooklyn Navy Yard — at the site of today’s Steiner Studios. Hundreds of historic views of the Wallabout Market are now available for perusing after a major digitization project by the National Archives wrapped up in 2020. At the venue’s peak, in the early 20th century, it was the second largest wholesale food market in the world.

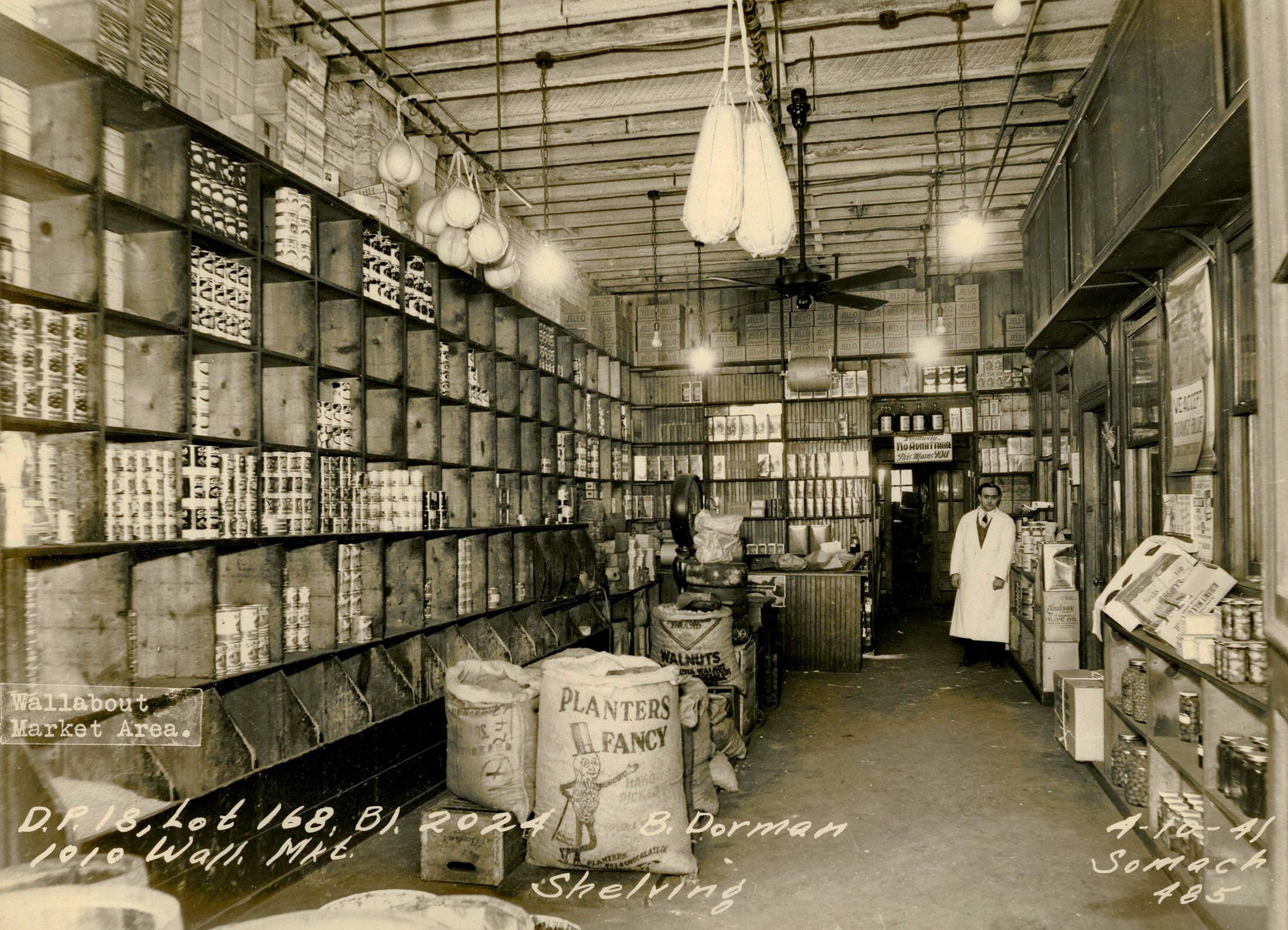

The market was a bustling place where produce, meat, dairy, fish and foodstuffs were sold and traded to the thousands of retail grocery stores, food shops, restaurants, institutions and other wholesalers who came there every day to haggle, buy, pack up and deliver. Similar to Hunt’s Point, the old Fulton Fish Market and the Brooklyn Terminal Market that replaced it, Wallabout Market was a world unto itself — a rough and tumble world that also included graft, corruption and crime.

But the market had one big advantage over New York’s other markets: it was beautiful.

Wallabout got its name from the French-speaking Walloons of Belgium who were the first settlers on the bay. They arrived in 1624, along with the Dutch, who called their bay Waal-bogt. The bay was the perfect location for the first ferry across the East River to New Amsterdam, which cast off in 1637, and continued for centuries. The area remained rural through the Revolutionary War, with most of it belonging to the Ryerson family.

The waterfront was an excellent port, which the British took advantage of when they took over Manhattan and Brooklyn during the Revolutionary War. Wallabout became infamous as the docking area for the British prison ships holding American soldiers and sailors throughout the war. Over 10,000 prisoners died on those ships, only to be dumped overboard, or buried in shallow graves on the shore. Today, the Prison Ship Martyr’s Monument in Fort Greene Park holds their remains and honors their memories. After the war, much of the Wallabout area was purchased by John Jackson. He and his relatives decided to open a shipyard.

The new United States government was interested in a permanent shipyard in New York, and bought 40 acres of John Jackson’s property. They kept buying more and more acreage, so that by the 1850s, the Navy Yard had been pretty well established, with the first dry dock, the Commandant’s House, the Navy Hospital and other buildings on site. The Yard became one of the area’s largest employers, and houses, tenements and related businesses grew, filling up the streets of the Wallabout neighborhood.

The streets and avenues nearest the yard became home to more and more industry. Factory and warehouse buildings soon supplanted whatever homes were closest to the bay. After the Civil War, many of the businesses were related to the grocery and food industry, with bakeries, wholesale grocery warehouses, cold storage facilities, packaging factories and other food related businesses predominating. It didn’t hurt that the sugar refineries of Williamsburg were right next door, either. The tantalizing smells of candy, sweets and baked goods wafted through the air, along with the less pleasant smells of the area.

The sugar refineries weren’t the only reason for the area’s food-related flourishing. It was very convenient for transportation. The streets were wide. Ferries could transport goods across the East River to Manhattan, and after 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge made surface transport easier as well. In 1888, the Myrtle Avenue El was completed, making the area an easy commute for workers. They could also take advantage of the many trolley lines that led to the Navy Yard.

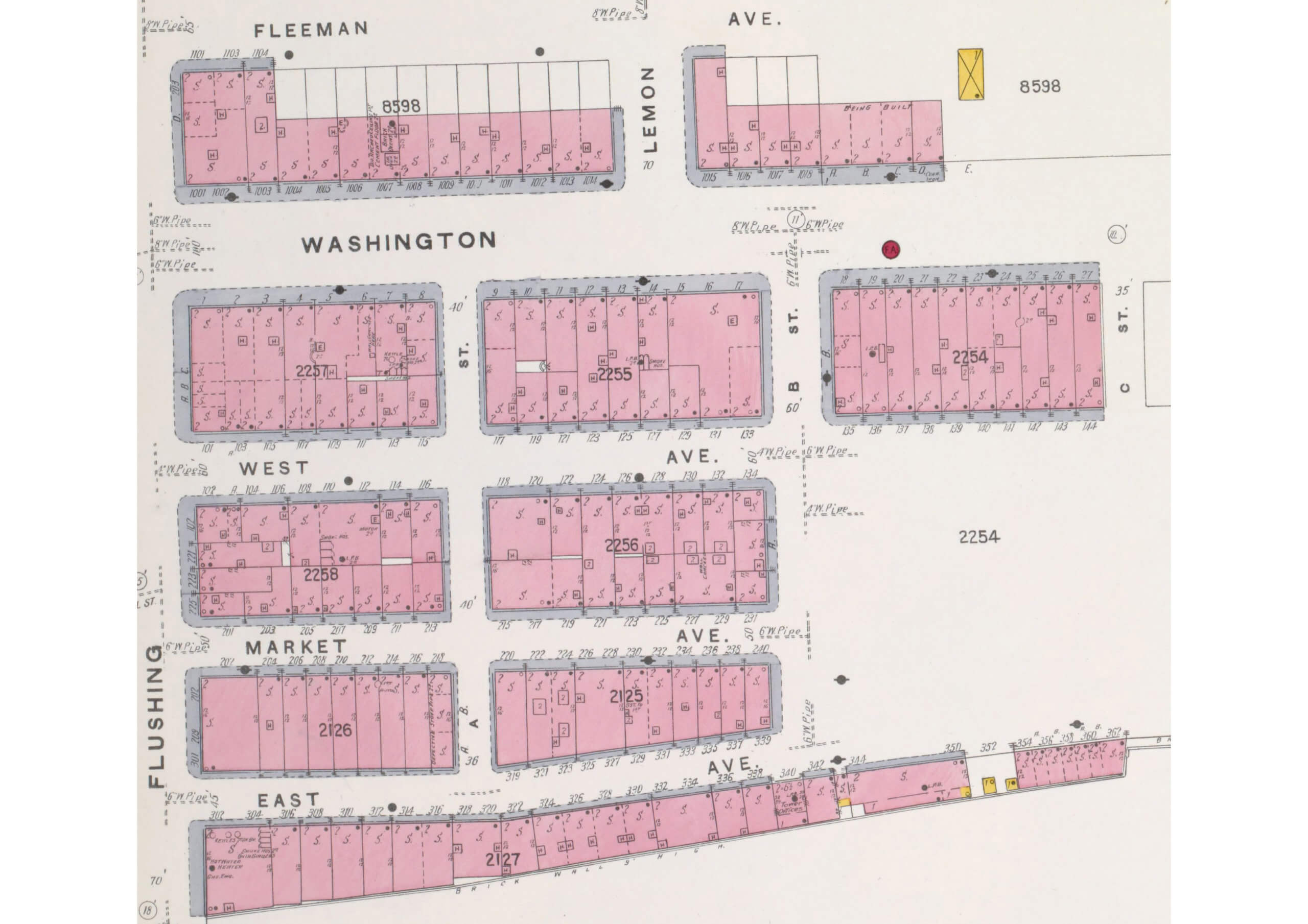

By 1884, a wholesale produce, meat and provisions market was in place in Wallabout. It was located north of Flushing Avenue, roughly between Washington Avenue and Ryerson Street. It had just been tossed up, with not much rhyme or beauty, with wood-framed garage-type buildings, as well as a few brick structures.

Time for a market with style

As the market was continuing to grow, the city of Brooklyn decided that it was time for a new physical market to be built, one worthy of this great city and its fine architecture. They hired William B. Tubby, whose work and friendship with Charles Pratt, Brooklyn’s wealthiest man, and nearby landowner, no doubt gave him an edge in getting the job.

As one of Brooklyn’s finest architects of the day, the thoughtful and innovative Tubby was well up to the task. He could have just built a few rows of utilitarian brick stalls and two story warehouse buildings, and collected his money, but he wanted more for Brooklyn and Wallabout Market.

Referencing the area’s Walloon and Dutch past, he designed an entire village of uniform brick buildings with a central plaza. All of the buildings had the familiar Flemish stepped roof motif on the sides and fronts, with decorative spires. They were arranged on four streets stretching from Flushing Avenue almost to the water’s edge. The new market was constructed between 1894 and 1896. It opened with great fanfare and celebration.

The heart of the “village” was a large building with a prominent clock tower and an almost fairy-tale conical spire on top. Its façade mirrored the ziggurat pattern of the roofs, but exaggerated for thematic emphasis. The buildings around the tower all had stalls that opened out to the market, their storefronts covered with permanent wooden awnings. Although the merchants and buyers in this bustling village were mostly wholesalers, there was a retail component near the clock tower, with a wide plaza for pushcarts and vendors. Shoppers came here for meat, produce, dairy, seafood and even plants and flowers. The idea of the farmer’s market is as old as civilization.

Cutthroat commerce in the fairy-tale market

That part of the market, and the hustle and bustle were the stuff of postcards and photographs, but the business of Wallabout Market was cutthroat commerce. There was a lot of money to be made here, and not all of it from selling one’s wares.

There was theft, graft and corruption a-plenty over the years. Thieves tried to steal merchandise, and also laid in wait for the tired farmers in their wagons to get ready to go back to their farms in Queens and Flatbush after a long day selling their produce. Many people were robbed somewhere between Wallabout and farther out on Long Island — one Jamaica farmer was killed right near his home.

There was also a lot of extortion, kickbacks and shakedowns. Some of it was from organized crime, some from street toughs, and some from those who actually ran the market. The Brooklyn Eagle chronicled stories of farmers who wanted to organize and band together to fight the extortion, but frequent “accidents” soon put an end to that. It was hard enough farming and getting your produce to market every day.

Insider corruption

In the 1930s, the papers, including the New York Times, were full of the activities of George Dressler, one of the last directors of Wallabout Market. Investigations of his operations showed misappropriation of funds, and monies gathered for a merchants’ emergency fund disappearing.

Mr. Dressler, the only person with access to the money, was unable to remember what happened to it. The investigations continued, there was a trial, but he was eventually cleared. He died an 80 year old man in 1944 with no mention of the scandal in his obituary.

Close of Wallabout Market over fear of spies

But the end of Wallabout was near. By the 1940s, with World War II escalating, the Navy Yard reclaimed the Wallabout space. They needed to expand, and also needed to be able to secure the Navy Yard’s boundaries.

Wallabout was too open, and spies and saboteurs were reportedly everywhere. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was one of America’s most important military bases. Wallabout would have to go. The city hastily decided to establish a new market at the Brooklyn Terminal.

On June 14, 1941, the commandant of the Yard, Captain Harold V. McKittrick, joined members of the Department of Markets as well as former tenants of the Wallabout Market in a ceremony to mark the passing of Wallabout, and the opening of a new Brooklyn Terminal Market at Remsen Avenue and East 87th Street in Canarsie. The ceremony included a 500 truck and car parade traveling from the old Market to the new. Mayor LaGuardia and other officials opened the new market that Monday.

Wallabout was promptly bulldozed. With the war raging and the space needed, there was little sentiment for saving anything in the market, not even the clock tower or its clocks; nothing survived. Factory buildings were built on the site for the manufacture of war materials and supplies. Today, the Steiner Studios complex and the surviving factory buildings stand where merchants once loudly hawked their goods, and thousands of people made a living from the bounty of the land. It looks a little sparse over there now. Perhaps Wallabout could come back?

Related Stories

- A Whimsical William Tubby Design for Brownsville’s Bastion of Knowledge, the Stone Avenue Library

- The Neo-Jacobean Prospect Park West Manse That Cleaning Powder Built

- 15 Architects Whose Designs Shaped the Look of Historic Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment