Walkabout: About Those Windows, Part 1

From a practical perspective, window treatments give a home the following: protection against rain and wind, drafts and cold air in the winter, and strong sunlight and heat in the summer. Window treatments also offer privacy from outside eyes, keep bugs, crawling and flying things out and add beauty to the rooms they are in.

Read Part 2, Part 3, Part 4 and Part 5 of this story.

Those of us who love old houses in all of their different styles and architectural variations, are often confronted with what can be difficult choices when we are furnishing and decorating our homes. Some people feel that a period look is the only acceptable choice, others feel that a modern approach is in line with living in the 21st century, while others may take a more eclectic view. From time to time, in this column, I’ve given historical perspective on the things in our homes that we talk about, and spend a great deal of money on. Bathrooms, kitchens, lighting, floors and ceilings have all been topics here. Today, I’d like to talk about window treatments, from an historic perspective. In examining what was original to our homes, we may get a better idea of what we might want to have now.

From a practical perspective, window treatments give a home the following: protection against rain and wind, drafts and cold air in the winter, and strong sunlight and heat in the summer. Window treatments also offer privacy from outside eyes, keep bugs, crawling and flying things out and add beauty to the rooms they are in. Now by window treatments, I’m talking about anything in the window box. That includes shutters, shades, blinds, screens, awnings, curtains and drapes.

Looking at the houses we have here in Brooklyn, that many of us live in, we’re talking about homes built in the late 18th through early 20th centuries. Two hundred years of architecture, and amazingly, there really has not been all that much change in window treatments. Much of what was familiar in 1840 is familiar today. Let’s start with blinds.

Chroniclers of late 18th and early 19th century domestic doings called everything pertaining to window coverings blinds. Interior and exterior shutters, Venetian blinds, exterior awnings, roller blinds, various kinds of shades, all were lumped together as “blinds” in the literature, so sometimes it’s confusing to modern researchers, as we tend to think of “blinds” in only a limited and specific way. But call them what you will, all of these window coverings were in use.

Exterior shutters have been misused, as the use of them as decoration, popularized by the Colonial Revival, has thrown off our sense of how these shutters were actually used. Most of the shutters we see today were never meant to actually cover the windows they frame, but that’s what they were originally meant to do in our early frame houses, providing protection against the sun and rain, privacy and security. Very few period homes today, especially up here in the North, have working exterior shutters.

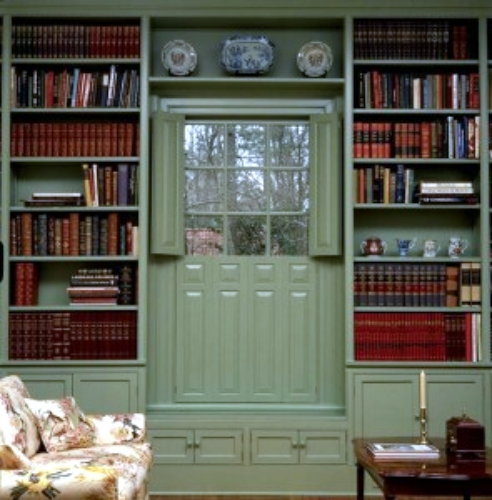

Interior shutters still are in use, however. Almost every row house built in this city once had interior shutters in the front rooms, facing the street. Most of us count ourselves lucky if we still have them, and it’s a special treat to find them, especially when they have been painted into their box frames for close to a hundred years. What a moment to cut them out of their painted cases, open them, and discover that the shutters within have never been painted, and all their louvers and mechanisms are intact.

There are several different styles of interior shutters. Some are solid wood all the way across. These would generally be found in earlier homes, before shutters were mass produced, and factory cut pieces assembled. Solid shutters could also be found in later homes protecting windows that could be seen from the street. Often the bottom shutters were solid, while the upper ones had adjustable louvers. As window sizes grew and shrunk, builders came up with interesting ways to divide the shutters, and there was usually an upper and lower set, to allow for the seasons, the amount of protection needed against the sun, or for privacy.

By the 1870s, when the Italianate brownstone was king, the “box shutters” as the encased shutters were called, were standard. Movable louvers were also standard, allowing the slats to be adjusted to allow light and air in, but maintain privacy from the outside world. Although other draperies were also highly popular, and we’ll get to that, the shuttered window was the common window covering for the Brooklyn home. Well, for the front windows, anyway. But that was not the only option.

We all are familiar with Venetian blinds. Today they come with metal or plastic slats, or new honeycomb slats. They are also now vertical, not just horizontal. But the classic blind — wooden slats connected by woven tapes and cording, mounted to a wooden frame — have been in use since the mid-1700s. Venetian blinds came in two different styles. One was the style we know today, the other had the blinds running in tracks on both sides of the window. These came in both interior and exterior versions.

Venetian blinds could be made to cover any size window, or any shape. Because the wooden slats were suspended from tapes, and manipulated by cording, fan shaped shades for Palladian windows could be made, as well as narrow shades for side light windows. The opportunities were unlimited, and as manufacturing techniques made the shades more affordable, they were quite popular amidst the 19th century’s upper middle class and above.

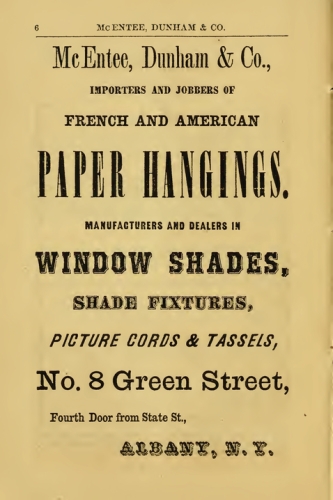

Mass production made Venetian blinds slightly more affordable, but they weren’t cheap. The average home had a less expensive alternative, one that is also still with us today, as well; the roller blind. Spring blinds were invented in the 1830s, and were mass produced by the 1860s, but most homes had pulley operated blinds throughout the 19th century. Roller blinds could be had by almost anyone, they could be made at home, and the coverings could be any commonly available fabric. Linen, canvas, gauze, calico, prints, cotton lawn, any of these could be used.

Godey’s Lady’s Book and other magazines offered instructions on how to make shades, and how to embroider or crochet trim for the bottom, and the pull chain. Ladies were encouraged to paint the shades with scenes from nature, or flowers and birds. Factories began producing shades in quantity, and every home had them somewhere, they were easy to put up and take down for washing, and kept the sun out, privacy in, and even kept some of the bugs out of the house in summer.

Those who couldn’t afford good quality cloth shades could find brown paper shades, or make them, as manufacturers began producing paper in common widths for windows, offering paper with printed borders. One only needed to measure the amount needed for the window, and affix it to the rod. Some homeowners began pasting wall paper to paper and cloth shades, making patterned shades, and that idea too, began to be popular with manufacturers.

This spurt of creativity didn’t suit the high end tastemakers of the day. Andrew Jackson Dowling, the great landscaper, lover of Gothic Revival architecture, and tastemaker thought the painted landscapes and patterned shades a tad gauche, as the shades covered up the wonders of nature outside the windows, but even he had to admit that if one was not amidst nature, as in a city, the patterns would bring nature inside. Today, we still use patterned fabrics and prints on our shades. A good idea can outlast even the best tastemakers.

The last form of shade used by the homemakers of the mid-19th century was the metal mesh shade. We still use them. They were made to keep bugs out, just as they do today. But since we are talking Victorian taste, and about a love of ornament and pattern, these metal screens, called in the writings of the day “wire blinds,” were not just put into place, they too, were often painted with landscapes and scenes.

So what about the yards and yards of draperies, the lace curtains, and the entire Victorian window excess that we associate with the period? We’ll talk about all that as we continue next time.

(Above ad: Hoxie.org)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment