Building of the Day: 2021 Bergen Street, a Brutal Brutalist School in Ocean Hill

Brooklyn, one building at a time. How does architecture affect the community? And in the case of a school, how does it affect the quality or the atmosphere of learning? Name: Intermediate School 55, now Brooklyn Collegiate High School Address: 2021 Bergen Street Cross Streets: Between Thomas S. Boyland St. and Rockaway Avenue Neighborhood: Ocean…

Brooklyn, one building at a time.

How does architecture affect the community? And in the case of a school, how does it affect the quality or the atmosphere of learning?

Name: Intermediate School 55, now Brooklyn Collegiate High School

Address: 2021 Bergen Street

Cross Streets: Between Thomas S. Boyland St. and Rockaway Avenue

Neighborhood: Ocean Hill-Brownsville

Year Built: 1965

Architectural Style: Brutalist

Architect: NYC School Construction Authority

Landmarked: No

Many of the public works of architecture built between 1950 and 1970 have been classified as Brutalist. It was originally named as such to describe the then-modern building style based on the architecture and ideas of the highly influential French architect Le Corbusier.

The Brutalist School

Reinforced concrete was the material de jour in the 1920s, and Le Corbusier called this new material béton brut, or raw concrete. In 1949, a Swedish architect named Hans Usplund was the first to use the term “brutalism” to describe a new housing project designed in Sweden.

The term was picked up by British architectural critic Reyner Banham, who penned a piece called “The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic?” in 1966.

Architecture, like any art form, is cyclical. Today’s styles are seen as vulgar and overdone (or underdone) by the subsequent generation, and styles change, sometimes quite radically.

The Brutalist movement of the mid-20th century was a reaction to the lightness and playfulness of 1930s and ’40s architecture. Art Deco and its descendants were optimistic, soaring with ornament and joy. The new architecture was solid, somber and totally without ornament or humor.

Brutalist architecture became commonplace for institutional buildings — schools, university and college campuses, hospitals, shopping centers, civic and government buildings, and public housing.

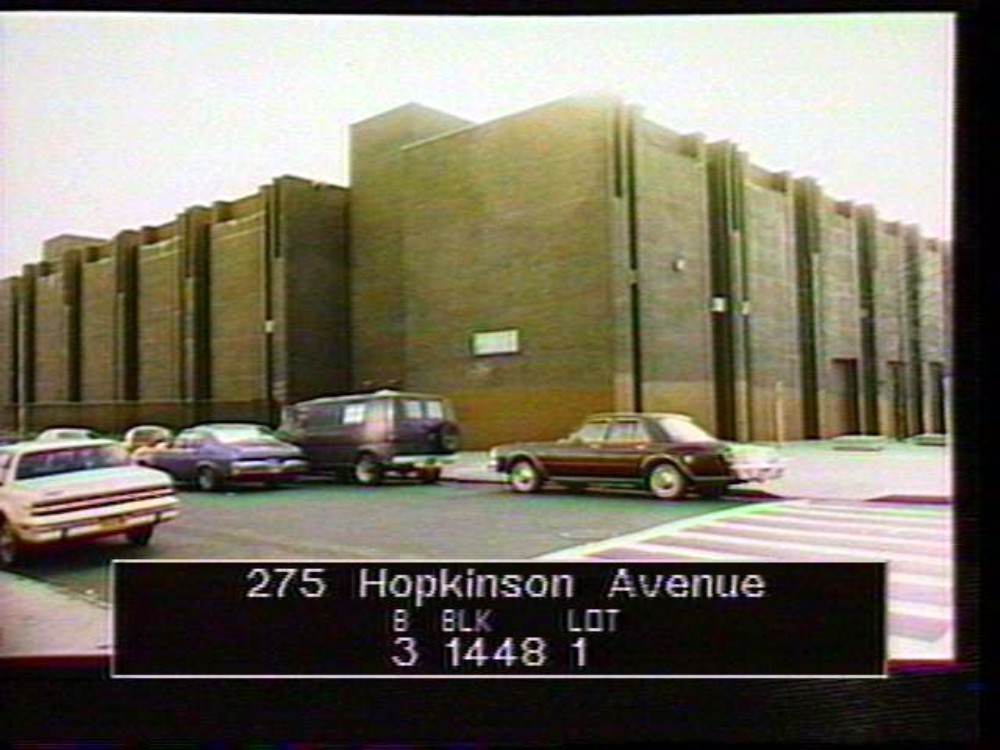

Early 1980s tax photo via Municipal Archives

New York’s Brutalist Civic Buildings

Here in New York City, Brutalism was eagerly embraced by all levels of government for public buildings. The city is littered with police stations, schools, firehouses, social service buildings, schools and housing in this stark and rather unfriendly style. But it was cheaper and thought to hold up well over time. It is concrete, after all.

There was a lot going on in the city during the 1960s, not much of it good. The inner cities were crumbling, both physically and socially, with police stations, firehouses and schools in need of upgrades.

At the same time, these institutions were under fire socially. Heroin was an epidemic nightmare, crime was out of control and, increasingly, the police were afraid of the communities they were charged to protect.

The schools in the inner city and poor neighborhoods were not teaching students, and parents wanted more control of the schools. This all would spill over into riots and, in 1968, the worst teachers’ strike in NYC history would take place here in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, one of the city’s poorest districts.

During this time, the city began building new precincts, firehouses and school buildings. They were all designed to replace the old Victorian and early-20th-century buildings, many of which still stand, either repurposed or abandoned.

Photo by Greg Snodgrass for PropertyShark

Intermediate School 155

This school was built in 1965, originally as Intermediate School 155. It is textbook Brutalist architecture. Only about four blocks away, at 1355 Herkimer Street, stands Public School 155, a five-story school building designed by C.B.J. Snyder in 1908.

Though the schools served the same community, the differences between them are stark. Snyder’s is typical of his design philosophy, constructed with steel-framed construction in brick, limestone and terra cotta, the school is a rectangle punctuated with banks of windows, to allow light and air.

The ceilings are high, the classrooms large and airy. Although there isn’t as much exterior ornament here as on many Snyder schools, it has a classic elegance. The building suggests that the authorities care about the kind of educational experiences here, it inspires learning, and looks like what we expect a school to look like.

P.S. 155 on Herkimer Street. 1908 photo via Brooklyn Public Library

By contrast, I.S. 155, now the Brooklyn Collegiate High School, looks like a prison.

The building is a large cube, taking up the block of Thomas S. Boyland Street, formerly Hopkinson Avenue, between Dean and Bergen streets. It was built on land purchased by the city for the purpose of building the school and establishing a public park behind it. Behind the park, facing Rockaway Avenue, is an FDNY station with a large EMS station.

The school is brick, not concrete, but the style is Brutalist. The building’s few windows are in narrow strips of aluminum cladding, broken up by portable air conditioners. The Brooklyn House of Detention has more natural lighting.

Photo via Google Maps

The entire school is a series of bunker-like rectangles. One side looks just like the others, and the unwelcoming entrance has no grandeur. If the building could speak, it would say, “Abandon hope, all ye that enter here.” What were they thinking when they designed and built this building?

There are a lot of Brutalist buildings in Brooklyn, not all bad, but this one is one of the worst. I can’t imagine going to school here, or teaching here. Four blocks away — that’s what a school should look like. This school — permanent detention.

A Few Thoughts on Architecture

And here’s the thing — architecture matters. We say volumes about what our society cares about by the buildings it builds for the respective communities in which those buildings stand.

The school system that erected C.B.J. Snyder’s elementary school wanted to inspire the poor and immigrant population in the area, mostly Italian and Jewish. It says that America was the land of opportunity and promise. This school was the beginning of a journey of success.

The new I.S. 155 gives an entirely different message. It is a fortress in an urban wilderness, guarding itself against the incursion of the ills of the poor, minority inner city neighborhood it stands in.

Defenders might say it was built that way with the purpose of cocooning children from the outside world, so they could learn without distraction. Plus it cost less to build without windows and fancy frippery.

A cynical person could almost imagine the building was preparing its students not for the promise of America, but the likelihood of a real incarceration. Was it really necessary to build a bunker, with down lights on the exterior that look like prison-yard lighting? Or is it only a building, with no hidden agenda? What say you?

Photo via Google Maps

[Top photo: Nicholas Strini for PropertyShark]

Related Stories

Building of the Day: 1677 St. Marks Avenue

Building of the Day: 49-65 Meserole Street

Walkabout: C. B. J. Snyder: New York City’s Master School Builder

There is no doubt that this building is an eye sore and doesn’t inspire much of anything, aside from thoughts of, “That’s where I’d go during nuclear fall out.”

However, the school building belies what takes place inside. I’m a science teacher at the Achievement First Brownsville Middle School that calls this building home and great things are happening inside. I’d venture to say that the love and learning had by kids and adults brings an ironic juxtaposition to the “brutalist” exterior.

The lack of light is rough. That won’t change. But what’s taking place inside makes its inhabitants believe iit the edifice was designed for a well-kept-secret, rather than as a bunker to protect the youth from society’s ills.

They should put out an RFP for a killer greenroof, with a hot house and a farm. Let gorgeous vines drape over the sides and plant ivy walls along the pavement periphery. It would certainly lighten it up and make it more inviting.

So sad. This building is the worst. It needs at least some murals or colorful tiles to wake it up and make it friendlier. As it is, what child (or person) would ever want to walk inside?

That’s easy to say if you’re not a student or teacher there. Tastes do change but the negative effects of a lack of natural light on human beings is consistent. In the mid 20th century, there was a sense that school designs needed to “eliminate distractions” from students which mean drab buildings with few or no windows. In retrospect that notion is absurd and even damaging but many of these types of schools remain. Style is subjective and you can say what you will about this school in that sense. But from a practical standpoint, this is a lousy place for teaching and learning.