Venture-Backed Grocery Delivery Apps Snap Up Shuttered Retail Spots From Brooklyn to the Bronx

Well-funded grocery delivery app startups are expanding rapidly across New York City, opening dark warehouses in large, ground-level spaces vacated during the pandemic that can serve a one-mile radius in the dense, typically upscale areas they target.

JOKR’s micro-warehouse or “dark store” in the Financial District. Photo by Gabriele Holtermann

This is the fourth story in amNewYork Metro’s five-part series examining the proliferation of grocery delivery services across the city — and the impact they’re having on residents and brick-and-mortar business owners alike.

New quick-commerce grocery delivery companies sweeping New York City have several things in common: they’re all app-based, their couriers primarily travel on electric bicycles and scooters, and their goal is to get customers their groceries within 20 minutes.

The speed of delivery is the backbone of their business model, and they accomplish it with “dark stores,” micro-warehouses stocked goods and groceries and placed in their target neighborhoods. Each dark store serves about one square mile, on average — about an eight-minute ride from the warehouse to the edge of the delivery zone.

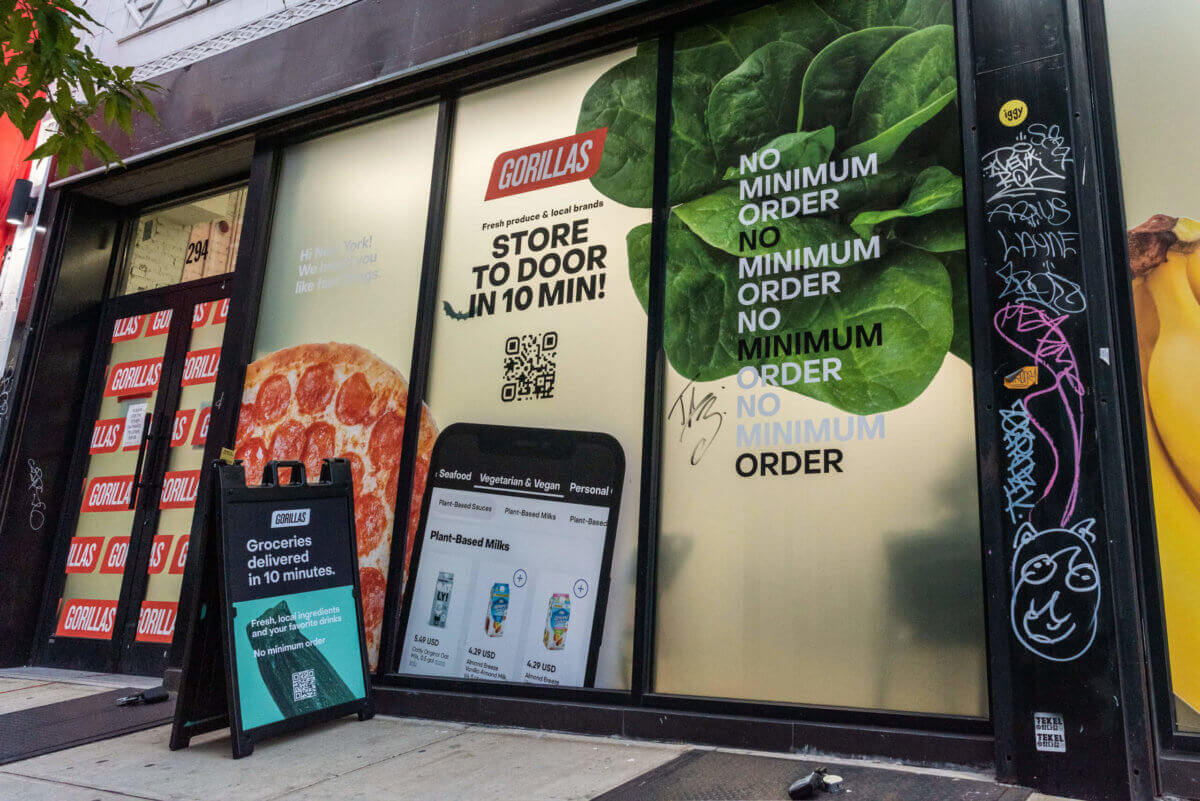

All launched in New York City in the past year, apps like JOKR, Gorillas, Buyk, and Fridge No More have expanded rapidly, and they’re not done yet — JOKR started up in June with only four warehouses and plan to operate 20 by the end of the year, and Buyk recently announced their expansion into Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, doubling their number of dark stores to 20 and making them the first of the companies with a presence in the northernmost borough.

At the heart of this rapid expansion is real estate. Any retail business needs space, whether it’s a warehouse or a storefront, and finding an empty space that checks all the boxes and won’t break the bank is a challenge in the city, especially in the neighborhoods occupied by the apps’ target demographics — mostly young families or professionals living in well-to-do areas like Williamsburg and lower Manhattan.

Alex Beard, a managing director with Ripco Real Estate, has worked in commercial real estate in New York City for 15 years. Earlier this year, he started working with Gorillas as they sought out available space for their dark stores, including a ten-year lease in the former home of a grocery store on the Lower East Side.

Gorillas is expanding faster than any other business he’s seen in his career, he said.

“This is new, as far as speed of expansion,” he said. “I mean, Gorillas’ motto is ‘Faster than you,’ so it’s not surprising that they’re expanding at the rate that they’re expanding. I started working with them in March of this year, there’s now 16 units in the city, and more coming, we have leases out.”

The low prices and increasing popularity of grocery delivery apps worry the owners of existing grocery stores and bodegas. While the pandemic saw grocery store profits soar, many bodegas are still struggling to recover, and one Brooklyn grocery store owner, who asked not to be named, said it’s likely easier for the apps to expand than it would be for a brick-and-mortar grocery.

“We’re looking for 60,000 feet minimum,” he said. “I’ve seen some delivery app pop-up locations where they’re taking advantage of empty commercial spaces in the city as a result of the pandemic. They’re putting up these gondolas, putting limited SKUs, and they’re off to the races on their e-bikes.”

A spokesperson for Buyk told amNY that the company has taken over a variety of empty storefronts, including some that filed for bankruptcy last year, like New York & Company.

Beard said looking for space for Gorillas isn’t necessarily easier than looking for a grocery store or other retailer. They need 3,000 square feet at minimum, and “at grade,” or level with the street — no steps up or down.

One thing that does work to their advantage is that they’re not looking for the most attractive, easily-accessible location, since the stores aren’t open to customers.

“We just need to be in ‘A’ markets, not necessarily at ‘A’ locations in those markets,” he said. “So we prefer side streets.”

Many landlords are worried about the prospect of delivery workers milling around outside the store, he said, but he hasn’t found that to be a problem — Gorillas employees aren’t gig workers like Uber Eats or Doordash employees, and the dark stores do have break rooms inside where couriers can sit down rather than waiting for their next order outside.

While Gorillas is certainly well-funded, they do have a cap on how much they’re willing to spend on a lease, he said. Getting started during the pandemic, when rents were lower, gave the company time to get a “good foothold,” he said, and the company was getting established before the boom of quick-commerce apps. As they’re just looking for storage, he said, Gorillas might get a little more “bang for their buck,” in terms of what they can fit in each location, since they don’t need to build out space for aisles and different departments for customers to peruse.

Manhattan landlords were concerned at first about leasing space to a brand-new company.

“Most New York landlords are pretty sophisticated, and you always have to weigh risk with any deal you’re looking at,” he said. “Gorillas, specifically, is very well capitalized by strong, strong VC backers. I think that helped to give landlords a lot of confidence in what these guys were doing.”

Some grocery stores are having the opposite experience, the Brooklyn-based store owner said. Finding a large and welcoming space is “crazy hard to find,” he said, and the spaces are pricey.

“Landlords would rather cut up a large space and charge more rent than get an anchor tenant,” he said. “Supermarkets are, margins are everything, right? When you’re paying rent in the millions, it makes a space look less attractive and appealing.”

Any company choosing to enter a market where rent is so high is probably catering to a more affluent clientele and has higher profit margins — he pointed to Whole Foods, estimating that the luxury grocer likely has a profit margin ten points higher than his store — and their stores in some of the city’s most expensive neighborhoods.

“The bigger you are, the more buying power you have, the lower your cost of goods,” he said. “There’s people who pass that on, it depends on the business model, pass it on to the consumer and the community, or they make a ton of money.”

So far, the well-funded startups have stuck to Manhattan and wealthier, trendier neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens – Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City. But Buyk, the most recent entrant to the grocery delivery game, has grown from six dark stores in Manhattan upon launching in September to 20 across four boroughs. Their locations in the Bronx are the first foray any of the apps have made into the northernmost borough.

Buyk chose to launch in Manhattan because the borough is “where the real-time retail concept is needed most,” the spokesperson said. Their goal has always been to serve all five boroughs, they said, and they plan to continue expansion in New York City before going nationwide.

Like Gorillas, Buyk’s ideal spaces are between 3,000 and 4,000 square feet, in a dense neighborhood but not necessarily on a pedestrian-heavy thoroughfare, and are preferable in an area where street infrastructure allows for efficient delivery routes. They also consider, of course, the price and availability of real estate.

They currently operate two dark stores in the northern part of the Bronx, covering Kingsbridge Heights, Norwood, Williamsbridge, Bedford Park, and Allerton, and plan to open more soon.

Radhamés Rodríguez, president of United Bodegas of America, said steadily increasing rents are a huge problem for corner stores, especially in the last decade. Even successful stores who need more space to keep up with demand often can’t afford to expand, he said, and some store owners who occupy larger stores split the space and rent part of it out to another business so they can make the rent.

“You’ll see, a lot of stores outside have flower shops too,” he said. “When you see that, you’ve got to know that’s because the rent is high. They do that just to get something to pay the rent.”

Rodríguez, who has been in the business for 30 years, said shorter leases offered by landlords are also a problem for store owners. Where a ten or 15 year lease used to be the norm, five years is now the longest most people can get.

“Before, you used to pay rent – it was $1,500, $2,000,” he said. “When I used to pay $2,500, that was a lot. But now, the minimum is maybe $3,5000.”

Some pay up to $7,000 a month, he said. He doesn’t blame the landlords — it makes sense for them to try to get the most of the space they have.

“The city, maybe they could do [something] to help the bodegas,” Rodríguez said. “Something, let’s say, through tax for the landlord so they could be more flexible when somebody is trying to rent something. It could help us to do that.”

The final installment in “The Race to Deliver” will examine labor relations between the companies behind the grocery delivery apps and their workforce.

[Photos by Gabriele Holtermann]

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in AmNY. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

- Bodegas and Small Groceries Fear Business Impact of Increasing Delivery Apps

- A Look at the Grocery Delivery Apps Taking Over New York City

- New Ocean Hill Urban Farm Will Provide Inexpensive Produce to Fight Food Inequity

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment