Welcome to Brooklyn's Sailortown, Ye Olde Tars and Salts

The men of Brooklyn’s Sailortown helped make Red Hook into New York City’s busiest port, and propelled Brooklyn’s economy and culture into a brighter future.

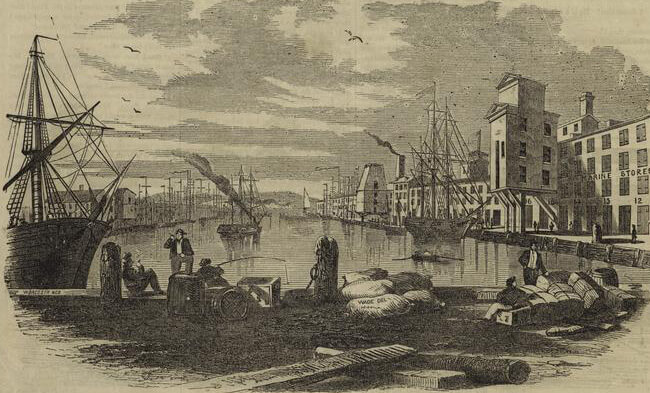

Atlantic Dock, circa 1872-1887 by George Bradford Brainerd. Photo via Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection

Mention the Red Hook piers today, and most people envision a quiet shoreline with walking paths leading away from the loft apartments, artist workshops and retail superstores. Stroll along the path and one can see the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, New Jersey and of course, over on the right, the towers of Manhattan.

There is also the harbor itself. Those now-popular lofts and artisan studios are the 19th century warehouses that once held everything from coffee to leather to cotton. The rotting piers that still jut out into the bay were once whole and bustling with workers moving goods from ships to warehouses and vice versa. The boards of the piers were groaning from the weight of men and their wagons and wheelbarrows, with shouts and curses in multiple languages from laborers from many nationalities.

Even as sailing ships and early steamships became more modern cargo ships, and bowler hats were exchanged for fedoras and newsboy caps, men worked these piers. Their labor powered the commodities markets of Wall Street, paid for the bosses’ mansions in Brooklyn Heights and Park Slope, and enabled generations of breadwinners to buy and rent in the houses and apartments of Red Hook and the rest of what was then known as South Brooklyn.

Moving back and forth from ship to shore for 150 years have been the sailors. They’ve been romanticized as wanderers with no home port, as troublemakers and rowdy drunkards, and as lost souls looking for love and perhaps salvation. When sailors make port, wherever they congregate becomes a “Sailortown.” Red Hook’s Sailortown was like many others in many ways, but its isolation away from the rest of the city made it special as well.

“It is not that life ashore is distasteful to me. But life at sea is better.” — Sir Francis Drake

We have always had a fascination with the sea and with those who sail it. Our popular culture has long made much of the ocean-going explorers who discovered new lands, and the captains of sailing ships who took advantage of trade to make fortunes for themselves and their nations. We’ve also held a soft spot for the rogues of the sea, as well, turning historically cruel and horrible people into folk legends and romanticized pirate lore.

By the beginning of the Revolutionary War, the American colonies, especially in the north, already had embarked on a shipbuilding tradition, with sailing ships built to ply the waters in the colonies, as well as across the Atlantic Ocean. In 1776, Red Hook saw the Battle of Brooklyn on its outskirts. The Colonial forces had fortifications on both sides of Buttermilk Channel, the body of water between Red Hook and Governors Island. Cannon fire from both sides enabled the Continental Army to escape the British as they fled New York. The waters off Red Hook were full of ships.

“Land was created to provide a place for boats to visit.” — Brooks Atkinson

Peace, and the growth of Brooklyn as a city of commerce and trade resulted in great growth of Brooklyn’s shoreline from Greenpoint down to Bay Ridge. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was established in 1801, and the Erie Canal, bringing goods from upstate and the Midwest, opened in 1825. In the 1840s, Colonel Daniel Richards saw the opportunity to build upon the natural landscape of Red Hook’s northern shore and built a harbor with docks and piers to capture this Erie Canal traffic. He called his company the Atlantic Dock Company, and the dock, also called the Atlantic Basin, was soon the busiest harbor in Brooklyn.

Ten years later, William Beard began establishing his own much larger manmade harbor called the Erie Basin. By the time it was completed in 1864, this protected port had 135 acres of docking space. The basin, and the brick and wooden warehouses that surrounded it, were packed with cotton, grain and other goods. The Erie Basin was also home to ship building and repair companies. The Fairway building and adjacent warehouses are all a part of Beard’s huge accomplishments.

Sailing and steam vessels docked offshore in New York Harbor. The goods being loaded or offloaded were first transferred to smaller boats called “lighters.” They were able to navigate the crowded waters of the basins and dock at the piers. Period photographs and illustrations of the day show the crowded harbor, the lighters passing between the ships, and those craft docked all along the harbor — with men, horses and carts moving goods all day and often at night.

“There is nothing more enticing, disenchanting, and enslaving than the life at sea.” — Joseph Conrad

Well into the 19th century, especially in New England and the Atlantic states, a life at sea for an American sailor was the stuff of boyhood dreams and legends. Going to sea was an opportunity for a young man to make something of himself. He could see the world, visit the great cities, and hopefully be a part of the crew of a successful captain or merchant who was appreciative of the skill and ability to deliver the goods in a timely manner. If he worked hard, or was lucky, he could become an officer and, someday, a captain. The wealthy sons of merchants also went to sea to make their fortunes. The Low family, the Pierreponts and others important to Brooklyn’s history and development were all New England-born seafaring merchants.

Of course, not everyone was there for adventure. The sea was also a place of escape for criminals and men who had no ambition or skill but signed up at the last minute out of desperation, boredom or to keep one step ahead of prison. The pace and stress of life at sea could cause some to turn to alcohol and drugs, others to turn vicious and cruel, and bring out the worst in them, especially when they were able to get on shore.

A life as a sailor attracted men from almost every land on earth, especially those countries that had long sailed their local waterways. By the time the end of the 19th century rolled around, steam ships were getting larger and larger, as were their crews. American companies not only contracted American-made and crewed vessels, but also ships from other countries. A crew coming into Red Hook could be a mixture of many nations. More and more, Europeans and other countries made up the majority of the crews working the merchant ships. When they landed and came on shore, they were sailors in Sailortown.

“They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; these see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.” — Bible, Psalms 107:23-24

More often than not, the sailors who docked in Red Hook were strangers to the city and to America. For the more secularly minded, a boarding house or sailor’s hotel was the best place to be. They offered reasonable lodging and a central place where the men could socialize and get a meal. They could also be job centers. Captains and recruiters knew where the lodgings were and often came to them to look for crewmen. A list of New York’s “Sailortown Hotels” printed in 1901 had 14 entries for Brooklyn. About half of them were in Red Hook, the remainder in the Atlantic Basin area, and the most northernly on Atlantic Avenue. Only two of the addresses are still standing: 355 Van Brunt Street and 94 Summit Street.

Some of these hotels were also epicenters of prostitution, grift and crime. While not every sailor led a life of drunkenness, rowdy troublemaking or crime, there were certainly those who did, giving all of them a bad reputation. With that in mind, many churches saw the sailors as a ripe harvest for the Lord. Local churches of many different denominations established mission churches in Red Hook, aimed at providing spiritual comfort as well as a clean bed and wholesome fare for sailors. Most of these missions were established in the late 19th or early 20th century. Several of them still exist to this day, and the buildings others established still stand as well.

Many of the sailors on merchant ships signed on in one country and when they reached New York, they were discharged, and had to find another ship going back to Europe or elsewhere. This system left a great many sailors on land, unemployed and often not speaking a word of English. Local churches and missions were often the only resource for those not inclined to spend their time on shore in drunken debauchery. Norwegians made up the largest foreign sailor population, with several missions devoted to their needs. One of the largest was the Norwegian Seamen’s Mission, which was located at 111 William Street, now Pioneer Street.

The church building had been built as a Dutch Reformed Church. The mission society was founded in Norway, and this church was established as the Sjømandskirken, the Seamen’s Church, in 1878. The church provided the seamen not only with an opportunity to worship in Norwegian, but also provided them with a taste of home, sharing meals and time with people who shared their culture and language. The church flourished in this location until 1928.

South Brooklyn had a sizable Norwegian population, most of whom had strong connections to maritime occupations, but by that time, most had moved from the area to Bay Ridge. The church moved to Cobble Hill, at the corner of Clinton Street and First Place. In the 1980s, the Norwegian population was scattered throughout the borough and suburbs, so the church relocated to East 52nd Street, where it still maintains a chapel and travel center for Norwegians abroad.

Pioneer Street is mostly residential now, cut off from Cobble Hill by the BQE. The church building became a warehouse and factory, losing its stained glass and decorative elements. It was abandoned in the 1980s, but has now been renovated, and is still an industrial space today.

The YMCA has several branches of their organization that catered to sailors. One was near the Brooklyn Navy Yard, another was on 46 Sullivan Street. It was called the Bethelship Seaman’s Branch and was built in 1921-22. The Bethelship was affiliated with the Norwegian Methodist Church. This building replaced an older church and rectory built by the Methodists in 1911. The hall was officially called the James Harvey Williams Memorial Hall. It was equipped with 94 dormitory rooms, restaurant, billiards room, showers and baths, reading and writing rooms, classrooms for religious education, employment office, and other activity rooms to keep a sailor on shore and out of trouble. A room cost 45 cents a night, or $2.80 per week.

The facility also had an infirmary, a barbershop, tailor’s shop, athletic facilities, and a locker room for storing one’s possessions. If a sailor died while at shore for any reason, the hall could also arrange burial or transport and notification of relatives.

The branch was active from 1922 to 1948. By then, the changing demographics of the Red Hook piers and the shipping industry as a whole had taken its toll on the resources of the branch. The arrival of the BQE didn’t help either. The building was sold and later in 1948 reopened as the Sullivan Hotel. Local histories also say it held government offices as well after the hotel closed. Today it is apartments with a daycare facility attached to it.

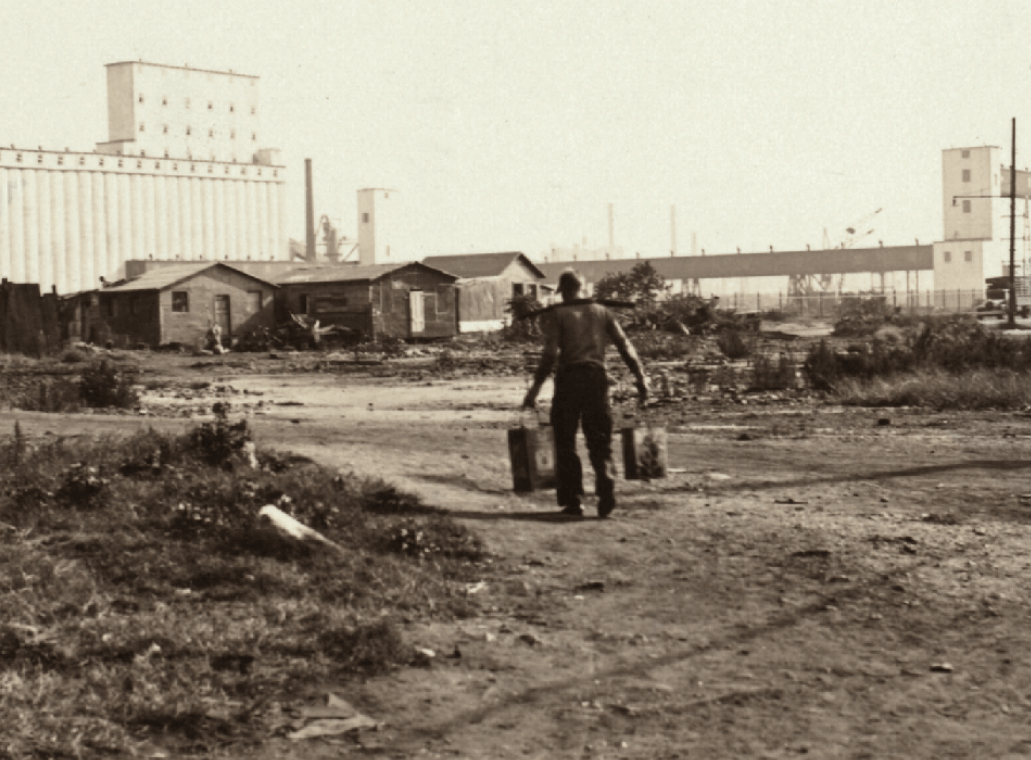

During the Great Depression, many of these Scandinavian sailors found themselves living in Hooverville shacks in the vicinity of today’s Red Hook Park. This story can be found here. They were the victims of poisoned whiskey, malnutrition and often died of exposure. The ships they had previously sailed on went home without them, dumping them on shore to avoid paying a full crew. They had to rely on these same churches and other charitable organizations to survive. Eventually public housing replaced the shacks, and a system of welfare and aid replaced uncertain charity. Shipping changed as well, with Red Hook’s piers practically empty after container ships began docking in New Jersey’s deeper waters beginning in the 1970s.

Today, Red Hook’s Sailortown is long gone. The days of tars and salts have passed into Red Hook lore and history, remembered only when looking for names for the latest trendy eating or drinking establishment. But these men, Norwegians and many others, helped make Red Hook New York City’s busiest port, and helped propel Brooklyn’s economy and culture into a brighter future.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment