Red Hook’s Lidgerwood Complex and the Importance of Our Industrial History

Preservation and landmarking efforts have mostly concentrated on residential and civic architecture and not our our rich industrial heritage.

Long before New York City’s groundbreaking Landmarks Law was passed in 1965, preservationists advocated all across the city for the protection of our historic structures. The passage of the law, which created the Landmarks Preservation Commission as a city department, made it possible to protect entire neighborhoods as well as individual buildings from the wrecking ball.

But for many years after 1965, preservation and landmarking efforts mostly concentrated on residential and civic architecture. The protection of industrial neighborhoods and the buildings in them never had the same cachet or sense of urgency that often helped protect row houses and mansions, apartment buildings and schools.

But our rich industrial heritage made those mansions and schools possible. The industries housed in these buildings made fortunes for their owners and enabled their employees to buy homes, rent apartments, shop for goods and services, contribute to their houses of worship, and put their kids through school. In the most direct sense of the word, industry built Brooklyn.

After World War II, Brooklyn saw most of its manufacturing plants close or relocate out of state. The factory buildings in South Brooklyn, Dumbo, Wallabout and Williamsburg, as well as in other neighborhoods, closed one by one, leaving a wealth of 19th century buildings available for new uses. Some were repurposed as warehouses and storage facilities, some were subdivided to house smaller businesses, and some just sat there locked and empty.

Some visionaries saw the potential in these buildings and neighborhoods. They bought as many as they could and repurposed them as housing and office space, stores and galleries, tying into new trends in urban living — loft space, and industrial chic. Neighborhoods like Dumbo and Red Hook became popular and populated once again.

But still, efforts to landmark many of the buildings in Red Hook and Gowanus were never as successful as they should have been. There was just too much resistance, and in many cases, an inability by authorities and the public alike to see the beauty or value of these buildings. They were just old brick factories and warehouses — placeholders for something better.

The Lidgerwood complex was one of those sites – just another large brick warehouse building in Red Hook. Most people couldn’t find it on a map, and if they could, didn’t know the name of it, and certainly didn’t know the history.

The site was purchased in 2017 by the United Parcel Service for $303 million for use as a distribution facility. Earlier this year, UPS razed part of the site and, subsequently, bowing to pressure from local residents and politicians, promised to rebuild it.

Advocates for the area had been fighting losing battles for years, as one by one, buildings that had been catalogued, researched and placed on “endangered” lists were torn down. The strategy of some property owners seemed to be that if it was endangered, better tear them down before those pesky preservationists got them landmarked, even if you had no idea what you were planning to do with the site.

So, what was the big deal with the Lidgerwood site? Who or what was Lidgerwood?

The Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company History

The company’s founder, John H. Lidgerwood, was the stepson of Stephen Vail, the owner of the Speedwell Ironworks of Morristown, N.J. The foundry, named after the sister ship to the Mayflower, was established in 1804 by Vail, who began his long career as a blacksmith. He and his forge were responsible for one of the earliest steam engines built for ships, as well as the engine for the Tom Thumb, the first successful steam locomotive built in America in 1829. Speedwell was also responsible for building parts for the first electric telegraph machine, as well as the machinery for the Savannah, the first steamship to cross the Atlantic.

John Lidgerwood’s widowed mother, Mary, was Stephen Vail’s second wife. She brought five children to the marriage in 1847, John being the eldest son. Vail put him to work at Speedwell, wanting him to learn the ironworking trade. He did just that, excelling in the business. When Vail retired, his son George took over. John Lidgerwood succeeded George as head of Speedwell.

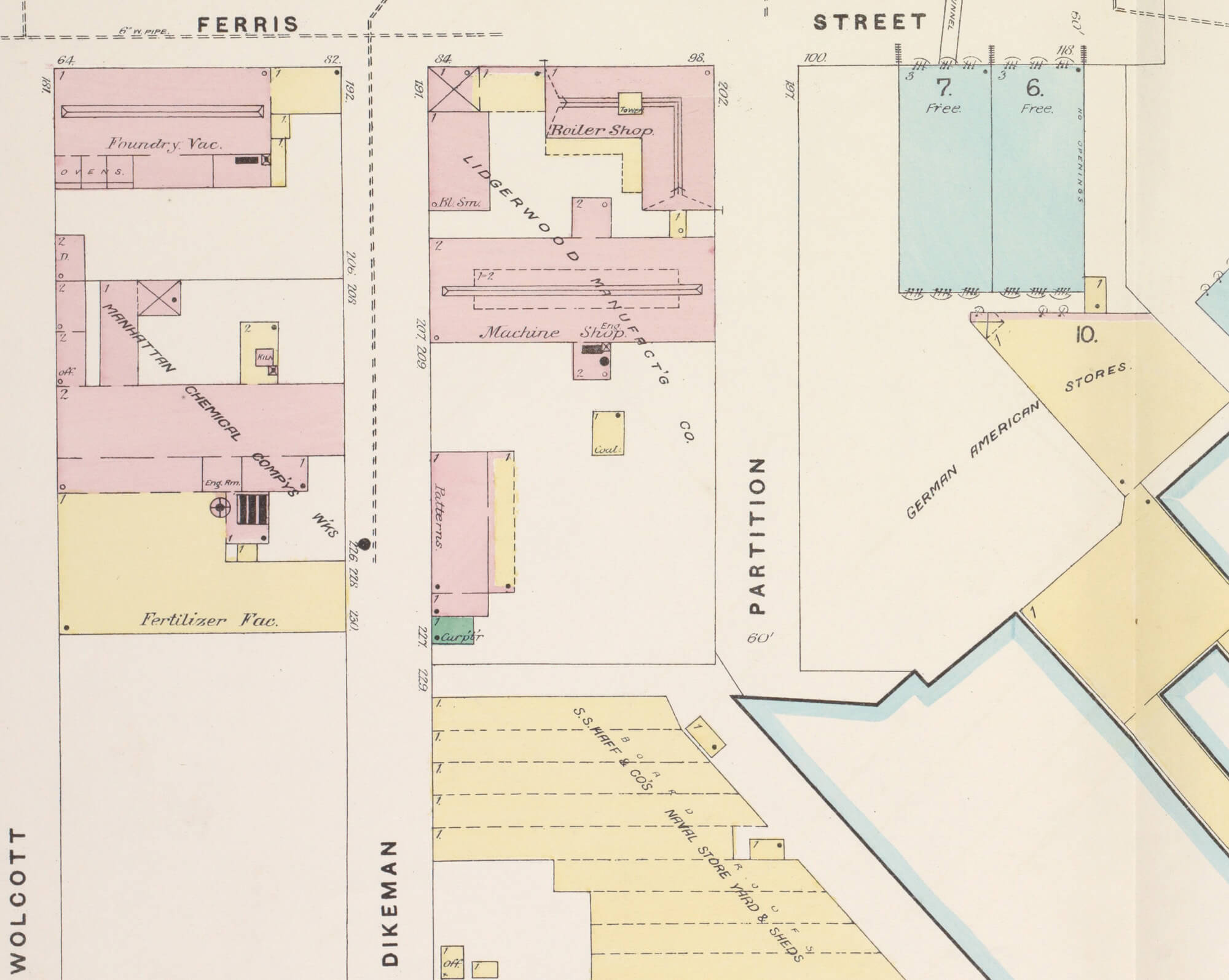

In 1876, Lidgerwood, his brother William Van Vleck Lidgerwood and son John Junior moved the company to Brooklyn, and also opened a Speedwell plant in Scotland. The New York company’s offices were in Manhattan. Their first building was much smaller than the familiar Red Hook building at 76 Ferris Street, but was on approximately the same site.

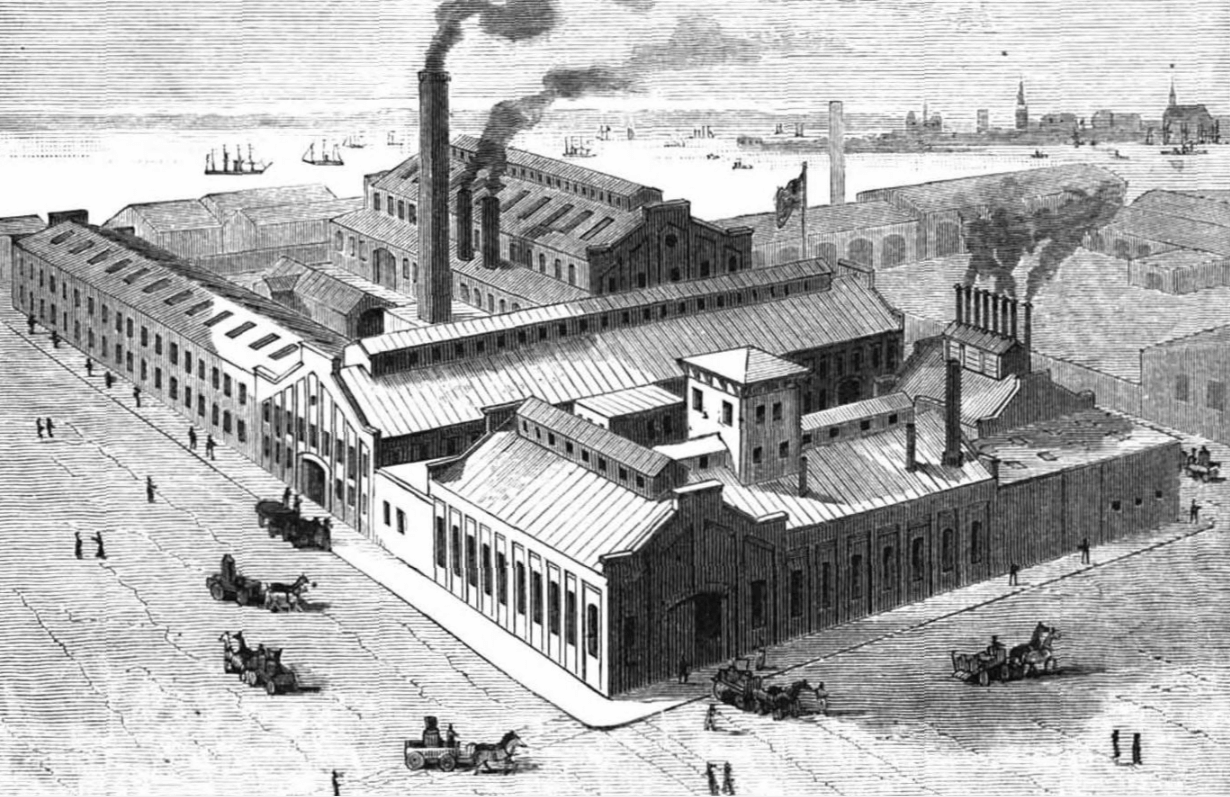

A much larger foundry was built in 1882 and was designed by architect John V. Beekman, whose name is also associated with the company for at least one machine patent. By now, the company had reorganized as the Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company. By 1883, they had more than 100 workmen on site and were planning an expansion of the plant.

Lidgerwood was not turning out small parts. They made huge, heavy equipment meant to help move heavy things. They specialized in marine and logging winches and they constructed enormous industrial coffee and sugar mill equipment such as cane crushers, boilers and general heavy lifting machinery, all powered by coal and steam.

The plant was enormous. An 1888 article in Scientific American Magazine described the plant in this manner:

“The main machine shop is 75 by 200 feet in size, and, with its gallery and two wings, affords a floor space of 28,750 square feet. The erecting shop covers a ground space of 50 by 228 feet, and with its gallery affords 17,500 square feet of floor room. The boiler shop is 50 by 100 feet, the blacksmith shop 45 by 90 feet, the Gorton heater shop 25 by 100 feet, and the storage shop 45 by 100 feet. Power is supplied by two engines, connected, but which may be readily disconnected, when either one will afford sufficient power for the entire establishment. All of the departments are completely fitted out with powerful traveling cranes, and the equipment in lathes and boring and turning machines of the latest patterns is designed to more than meet every possible demand.”

The Gorton heater was a commercial sized coal-burning boiler used in schools, homes, office and other large buildings for heating. It had its own division at the Lidgerwood plant. The magazine article was illustrated with plates showing workmen, many in bowler hats and caps, toiling in the various manufacturing and assembly rooms.

Even before the company moved its production to Brooklyn, Lidgerwood was selling equipment to Brazil, garnering so much business they opened a factory and office there. Both Stephen Vail and his stepson John Lidgerwood made trips to Brazil, establishing contracts for logging and cable hauling equipment, although through the 1880s, their largest orders were for Lidgerwood-patented coffee-hulling machines, which changed coffee production in that country.

The Company Grows, Building the Infrastructure of the 20th Century

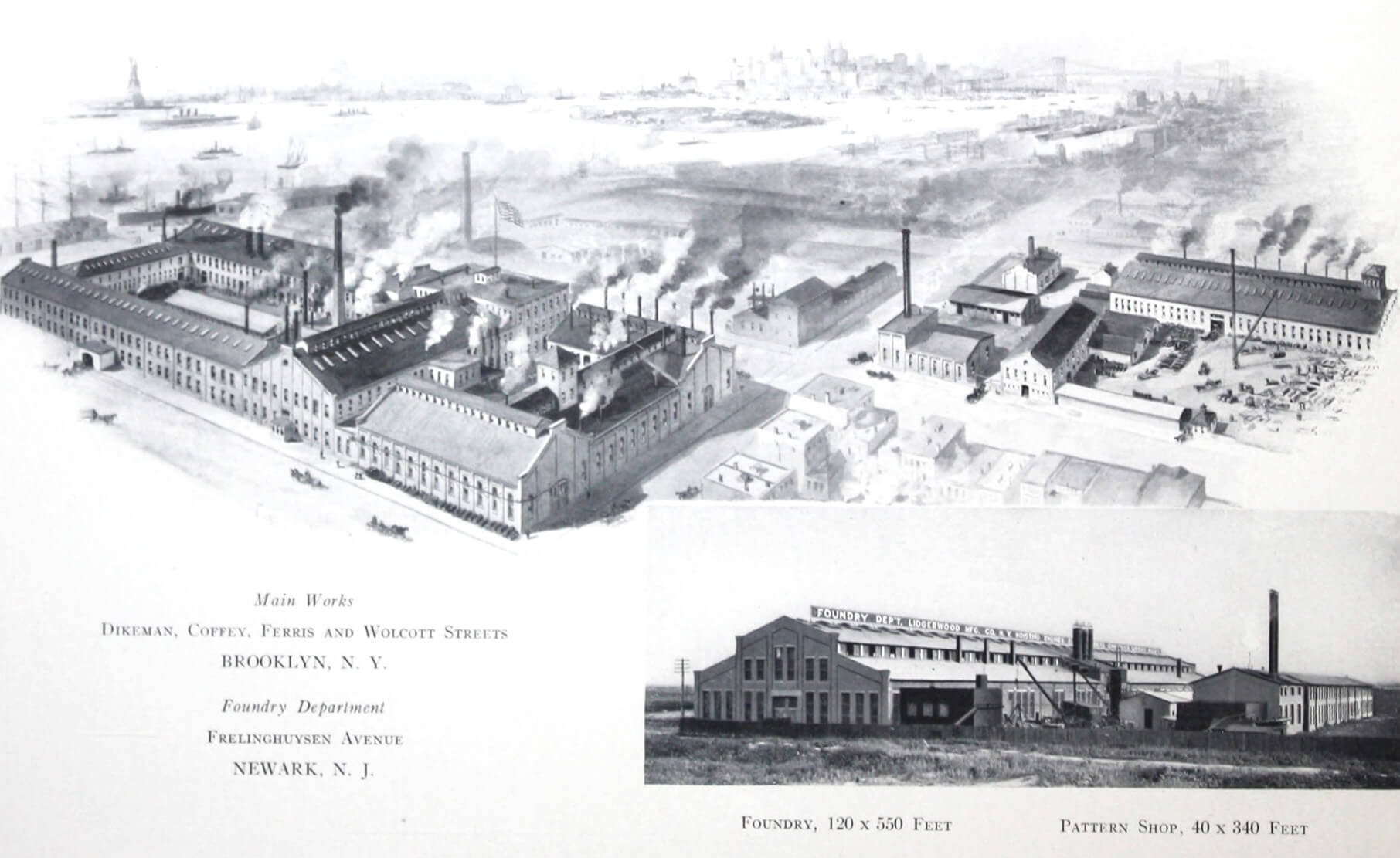

By the turn of the 20th century, Lidgerwood was best known for its heavy moving machinery. The plant now took up an entire square block bordered by Ferris, Dykeman, Coffey and Wolcott streets. They had expanded their branch offices and now had facilities in Boston, Chicago, Pittsburgh and Portland.

The latter city was an important site because one of Lidgerwood’s most successful pieces of heavy machinery was the Lidgerwood Logging Tower Skidder. This heavy-duty steam-powered rigging system allowed huge logs to be transported across the forest via a system of 85-foot-tall towers and cables and loaded by other Lidgerwood equipment onto trains and other transportation. The remains of a few of these systems still stand in the forests of the Northwest.

Much in the same way “Kleenex” is used to refer to facial tissues, “Lidgerwood” became a generic name for the log skidder and other rapid loading cable systems, throughout the logging, shipping and excavating world. The Lidgerwood name was on pile drivers, mining equipment and on the heavy-duty hoists in harbors everywhere, including across Red Hook and Gowanus.

In 1912, Lidgerwood Manufacturing published a bound book showing their cable hauling equipment in use in earth-moving projects around the world. They included important dams and canals across the world, such as the Panama Canal locks, Australia’s Cataract and Baron Jack Dams, and a dam in South Africa. In the U.S., cableways spanned the Croton Falls and Ashokan Dams, both part of New York City’s water supply system. The Roosevelt Dam, Kentucky River Dam, the Shoshone Dam in Wyoming, and other dams in Alabama, West Virginia, North Carolina and Washington State — all were built with Lidgerwood cable equipment.

Digging the Panama Canal would have been much harder without Lidgerwood innovations. Although some sources cite Lidgerwood as the sole supplier of heavy machinery at the canal, further research shows equipment from many sources was used, including some left on site by the French. They began digging the canal in the 1880s but were cut down by malaria and other tropic diseases. When the Americans restarted the project 10 years later, Lidgerwood products became part of the arsenal of tools and heavy equipment.

Worth special mention is the Lidgerwood Unloader. It was a three-ton plow hitched to the last car of a series of flatbed train cars piled high with dirt and stone. The unloader also included a winch device mounted on a flatcar at the head of the train. Powered by the train’s engine, the plow was winched to the front of the train, and then dragged to the end, unloading the cars in a single sweep that took only 10 minutes. Before the unloaders, engineers calculated that it would take 5,666 men to unload by hand the same amount of material handled by 20 unloaders and 120 men.

Going Forward

Of course, having this enormous and important business with branches in six cities and in several foreign countries came with great rewards for the company. The physical plant in Red Hook saw buildings improved, enlarged and joined, resulting in a block-filling complex that included several different foundry rooms, large assembly rooms, shipping rooms, a separate power plant, office, machine shops and a draughting room. At the height of the company’s success while in Brooklyn, they also maintained a series of buildings on a nearby block, containing equipment, coal, sand, woodsheds, a stable and wagons.

The buildings were all tall two-story brick factory/warehouse structures with high ceilings and a run of clerestory windows above, which let in natural light. The main foundry building had a wooden gangway that ran the length of both sides of the building and featured a cable system of its own, allowing the heavy manufactured parts to be carried along an assembly line from end to end.

This complex of separate but connected buildings evolved over the years, but there were also safety and fire considerations in the way they were constructed and aligned. A large courtyard in the center of the complex also allowed for more light and fresh air. Working here must have been incredibly hard, hot work.

The Lidgerwood family enjoyed their success. They never lived in Brooklyn, and always maintained their homes in Morristown, N.J. It wouldn’t be surprising to learn that the men maintained a hotel suite or two, either in Brooklyn or Manhattan, for times they couldn’t go home. In 1886, William V.V. Lidgerwood launched his steam-powered yacht, the Speedwell, in the nearby Erie Basin. The craft cost him $20,000, twice the price of building the average row house of the day. He was a member of the New York Yacht Club.

In the early 20th century, he and his family relocated to Glasgow and then to London to run the European operations of the company. Drawing on the family company’s origins, it too was named for the original company, the Speedwell Ironworks. The English branch of the company became know for engines for trawlers and tugs, as well as for their stationary engines for factories.

John H. Lidgerwood, the family patriarch and stepson of the founder, died at the age of 80 in 1910. His sons, John Jr. and James, inherited the company. The Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company left Brooklyn in the early 20th century, moving manufacturing out of state. The vast space was, at least in part, leased to other companies maintaining manufacturing foundries.

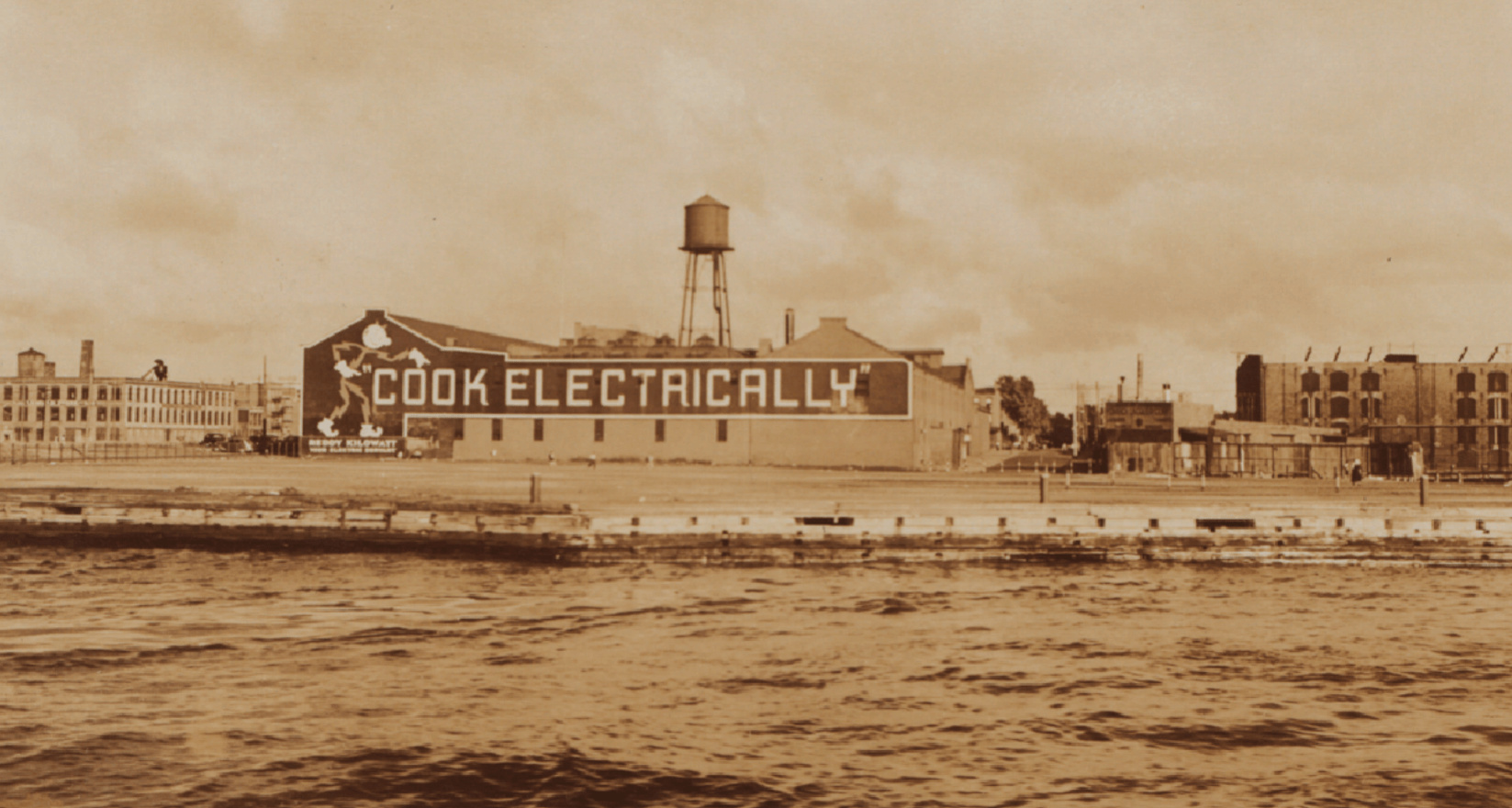

In 1926, the factory block, along with other nearby sites, was sold to Consolidated Edison, which planned to build a massive electrical generating plant. They held on to it at least until the beginning of World War II. Ads in local papers in the late 1930s tout the efficiency of electricity for home cooking. It is not known what Con Ed did with the building, since the electrical plant was never built. They may have continued to rent it out.

At some point, the clerestory windows on most of the buildings were removed, and the windows and many of the doorways were bricked in. As per many old industrial buildings, various parts of the Lidgerwood complex served as storage, small manufacturing and artist space.

In 1944, Lidgerwood relocated again to Elizabeth, N.J. In 1947, they purchased a Wisconsin ironworks company called Superior Ironworks. The two companies became the J.S. Mundy Hoisting Engine Company and Superior-Lidgerwood-Mundy. They moved all manufacturing to Wisconsin in the 1950s, and still maintain a New York office. Today, Superior-Lidgerwood-Mundy remains one of the largest manufacturers of marine winches and heavy lifting equipment. They remember with pride the history of the company and its contribution to Brooklyn’s economy and growth.

It is understandable any company needing a lot of space would be interested in Brooklyn’s industrial properties. It is unfortunate when the history and legacy of these important businesses are not considered, only the land they sat on. Historic industrial buildings can be adapted to new uses or incorporated into new facilities — an opportunity to make something special, while preserving our proud industrial past.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment