Beyond the Croton Aqueduct: A Story of New York City Water

The New York City water system supplies exceptional water to a population of 9.6 million in the city and surrounding communities.

Ashokan Reservoir

With the population of Brooklyn exploding from fewer than 100,000 residents in the mid-1800s to more than a million in 1900, pressure on access to freshwater brought it to a breaking point—and with it, the newly consolidated five boroughs of New York City. Manhattan had already experienced a cholera epidemic in the 1830s and loss of 17 square blocks in the Great Fire of 1835. Collect Pond froze over, rendering the water useless to firefighters and prompting the city to find an alternative source. That launched a quest to tame upland sources of fresh water for the rapidly growing city that continues today.

“Views from the Watershed,” a series of tours led by artist Lize Mogel sponsored by the Catskills Watershed Corporation, makes visible the trajectory of this expanding water system. From the mid to late 19th century, the Croton Aqueduct supplied Manhattan with 90 million gallons a day from a dam in northern Westchester County on the Croton River. With the late 19th century growth of the now-consolidated five boroughs, the State of New York passed the Water Supply Act of 1905 and began prospecting for sources of water in the Hudson Valley.

A key requirement for this water system involved identifying a source sufficiently elevated above ground level so that gravity alone could supply water to five- to six-story walk-ups without the use of pumps. One condition that recommended the Catskills was the extraordinary quantity and quality of its water. It was relatively close to sea, 100 miles upland, benefiting from rain and humidity, and it was high in alkalinity and softness due to being fed by hard-rock mountains, largely absent of limestone deposits. Its low corrosivity and mineral content would make Catskills water especially good for machinery, sparing industrial equipment from calcium buildup. It also explains a unique attribute of the city that other places find hard to replicate: its great bagels, which purveyors far and wide try to imitate by adding softeners and bases to water used in their production.

The city engaged in an aggressive policy of land acquisition by eminent domain. Starting in 1907, it began building the water storage and delivery systems, including the Catskill and Delaware aqueducts. By 1915 it completed the 125 billion gallon Ashokan Reservoir, occupying 8,315 acres in Ulster County, and now contributing 40 percent of the city’s water. The 140 billion gallon Pepacton Reservoir was operational by 1955, stretching 15 miles though 5,763 acres of Sullivan County, and contributing another a quarter of the city’s water.

New York City has reason to be proud of this extraordinary enterprise. It supplies exceptional water to a population of 9.6 million in the city and surrounding communities, as well as stewards the land it courses through. But it’s easy to ignore the impact this venture had on the communities in the Hudson and Delaware watersheds.

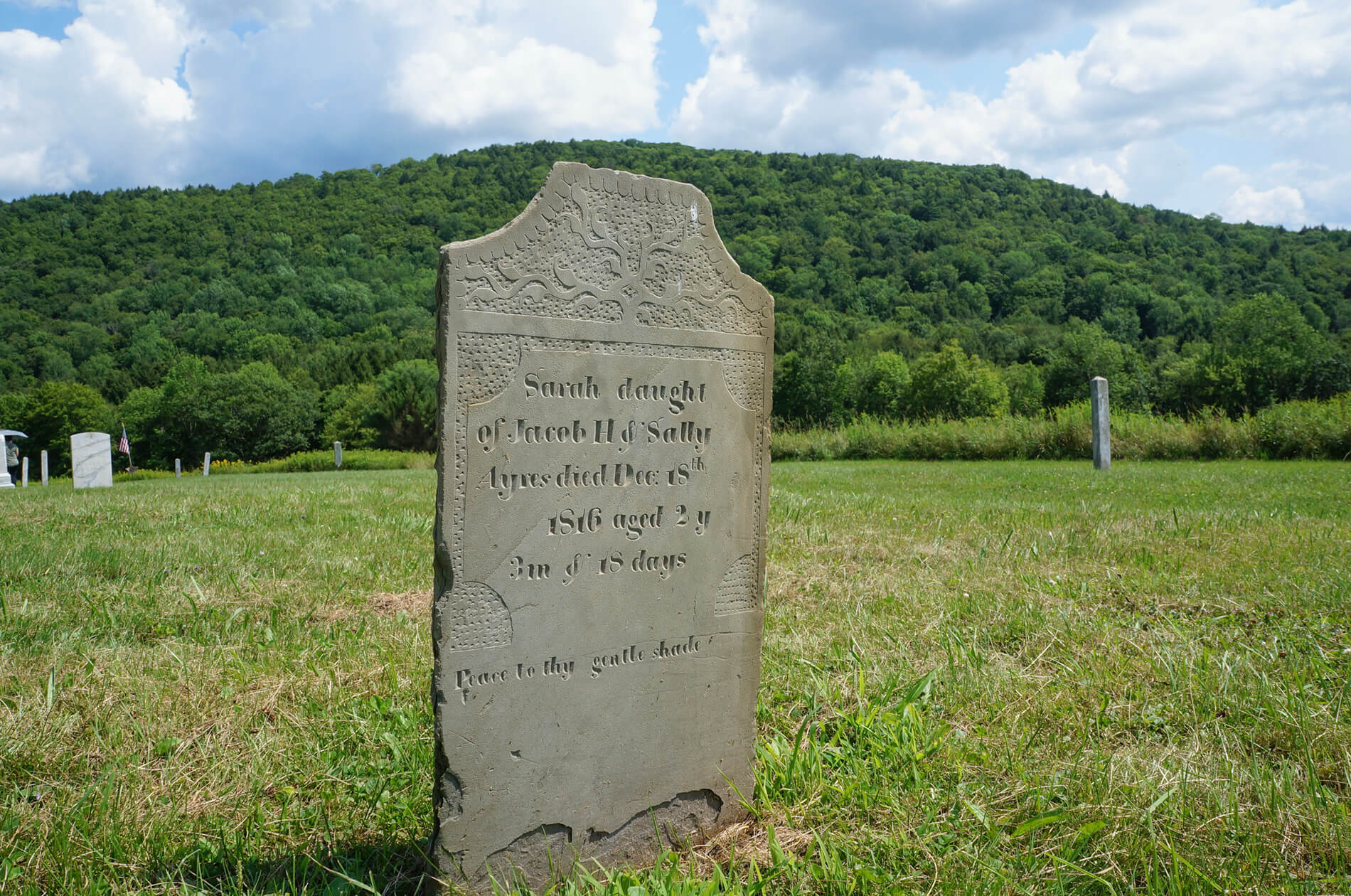

An odd byproduct of the early political wrangling was the exclusion of Dutchess County from access to the Catskills-Delaware Valley water system, in contrast to most parts of the region. As the city was prospecting at the turn of the century, Dutchess County’s landowners passed a law prohibiting the city from using eminent domain to acquire land in the area. For good reason: The project would eventually swallow up 12 towns within the footprint of the Ashokan Reservoir and three more within Pepacton, along with a large number of farms, churches and cemeteries. The 1905 Water Supply Act took revenge on Dutchess County by writing it out of the water system.

The Catskills Watershed Corporation formed in the aftermath of the latest chapter of this saga. In 1989, the Environmental Protection Agency adopted the Surface Water Treatment Rule, requiring most supply systems to filter and disinfect water to protect against viruses, bacteria and Giardia lamblia. That would have come at an astronomical cost to New York City, which argued for an alternate strategy: Using eminent domain to purchase and protect against sources of contamination.

It was an incredible power grab by the city extending well over 100 miles beyond its boundaries. The land acquisition required it to purchase hundreds of thousands of acres, systematically depriving those communities of their sources of economic livelihood. The property would be permanently unavailable for commercial development, limiting potential sources of employment for workers, prohibiting spreading of manure, and stifling sources of taxation to support local schools and roads.

In January 1997, after nearly a decade of pitched battles and negotiations between New York City, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Coalition of Waterfront Towns, the parties signed a memorandum of understanding. It ensured the communities a consulting role over the water system—led by the Catskills Watershed Corporation—funding for road and bridge repair and construction, the right to hunting and fishing from the shore or approved boats, building of trails, and development of tourist industries within the watershed. The city and other public agencies now own 285,000 acres of land within the Catskills and Delaware River Valley, amounting to 720 square miles of protected land.

The CWC is currently completing offices in Middletown, N.Y., designed by Keystone Associates, along with a 144-seat auditorium, a 700-square-foot Water Discovery Center, and a 33-acre nature trail. It will lease space to the New York City Department of Environmental Protection to manage and monitor the massive water system. It has a capacity of 570 billion gallons and 7,000 miles of pipeline to maintain, employing 6,000 workers throughout the watershed. The city plans to purchase an additional 80,000 acres in the coming years.

That, in brief, is the story of how New York City lays claim to having the largest unfiltered source of water in the United States.

[Photos by Stephen Zacks]

Related Stories

- Past and Present: Testing the Waters

- Past and Present: The Mt. Prospect Reservoir

- Brownstoner Upstate: Exploring Ulster County’s Ashokan Reservoir

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment