In the 1920s This Manursing Island Mansion Was Revealed as a Mistress's Secret Hide-Away

Delving into the history of a house with a bit of age often involves attempting to prove or debunk some entrenched mythology.

Delving into the history of a house with a bit of age often involves attempting to prove or debunk some entrenched mythology. In the case of this waterfront manse, the digging unexpectedly turned up a story endlessly more fascinating than predicted and a connection to a scandal that dominated newspapers across the country in 1922.

The early 20th century house on the market also has an unusual location, 33 Island Drive on the northern end of Manursing Island in Rye, N.Y. What exactly is Manursing Island? Perhaps before getting into the juicy tales, some background is needed on this bit of land off the coast of Rye, N.Y.

While it’s now connected to the mainland, in 1660, Manursing Island was a slip of land in the Long Island Sound on which a group of European settlers established the new town of Hastings. Before the end of the decade, the settlers had merged with the nearby town of Rye and had mostly moved off the island.

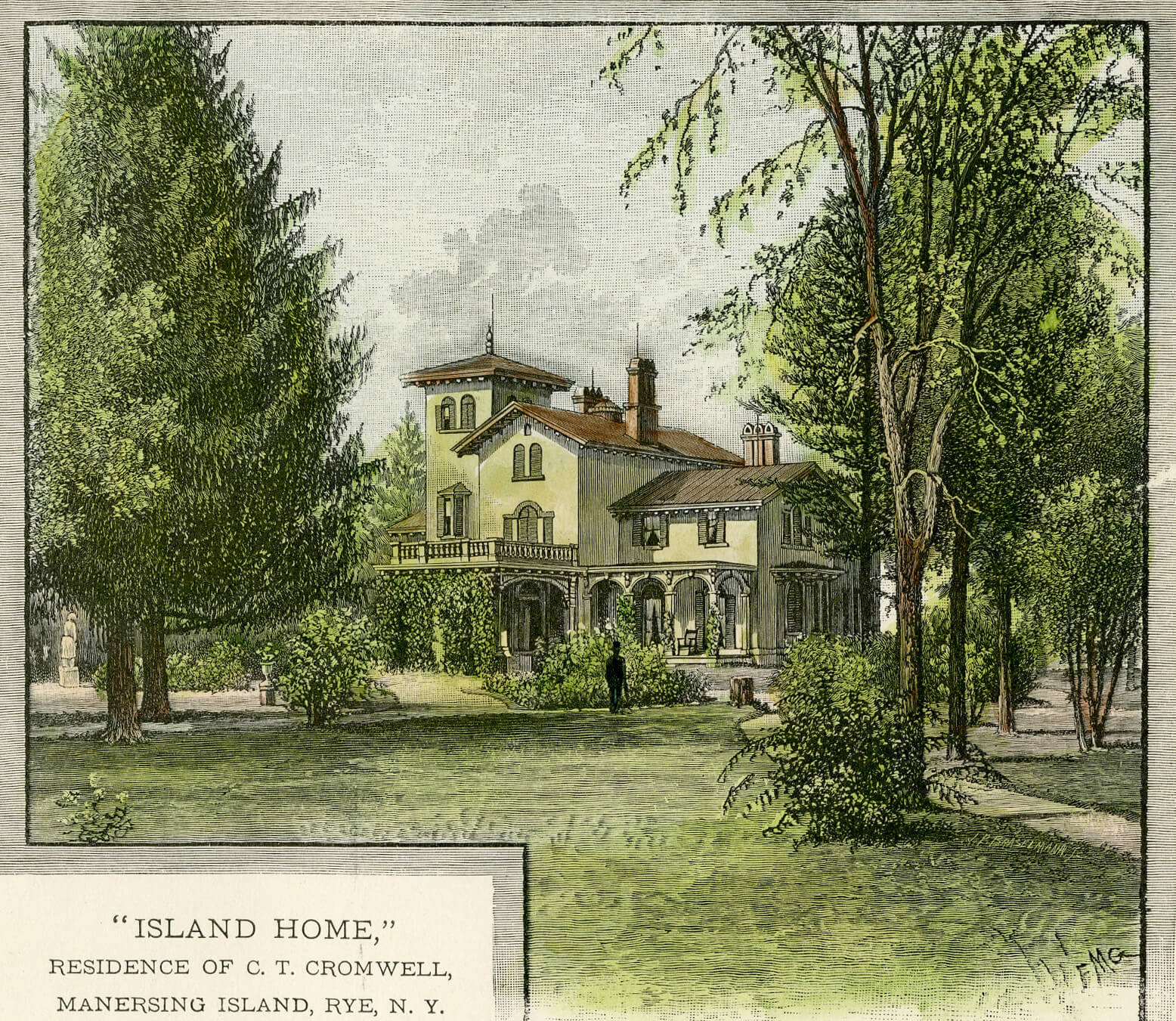

By the 19th century, the island was largely owned by just a few families with estates scattered on the northern and southern ends. One owner was lawyer Charles Thorne Cromwell who had a summer house on the northern end of the island. The listing for the house at 33 Island Drive claims that it was originally designed by influential American architect Alexander Jackson Davis and it may be the connection with Cromwell from which this story rises.

According to a list of Davis works compiled by Jane B. Davies and published in “Alexander Jackson Davis: American Architect 1803-1892,” Davis did design a villa and gardener’s house for Cromwell’s Manursing Island property in 1851. However, the author indicated that the design, if constructed at all, was either later heavily altered or demolished. A lithograph of Island Home in the collection of the Westchester County Historical Society certainly shows a Davis-influenced villa, whether any of it survived the construction of the current house is unclear.

Cromwell died in 1893 and his 17-acre estate was leased out until it was put on the market around 1904. Change was coming to the island at this time as land on the southern end was sold and developed with plans calling for a new bridge, club and housing. The Cromwell property was bought by J. G. McLoughlin and then sold by him in 1916. It is likely here that the connection to one of the Gilded Age’s wealthiest families begins.

Financier and “robber baron” Jay Gould died in 1892 leaving an estimated $72 million dollar estate — billions of dollars in today’s currency. His children, including eldest son George Jay Gould, came into a significant chunk of money managed by a family trust. George also inherited some railroad holdings but was perhaps not the ruthless businessman his father was, enjoying lavish spending on a very comfortable lifestyle.

George had defied some society expectations by marrying Brooklyn actress Edith Kingdon in 1886. Edith largely gave up her career, except for some private performances, and became a popular hostess on the social scene. She and George had seven children together and established homes on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue and a country estate in Lakewood, N.J. After more than 30 years together, everything changed on November 14, 1921, when Edith suddenly collapsed and died while playing golf with her husband on their estate in New Jersey.

Eight months later, on July 12, 1922, papers across the country blared the front page news that George Jay Gould had remarried. Newspapers were so quick to report on the shocking new marriage that details were not completely sussed out before publication. The wedding was originally reported to have taken place in Paris the week before and the new bride a former actress or showgirl of either American or English origin and named in some accounts as Alice Sinclair and in others as Vere Sinclair. Her hair was “burning red” or “golden blond” depending on which account you believed. Even her widowed status and the number and age of her children was up for speculation.

The New York Times ran the more sedate headline of “New Gould Bride Has Home on Sound and Two Children,” and reported that Gould hadn’t been married at any municipal office in Paris. They identified the new Mrs. Gould as Vere Sinclair, “who for the last few years has occupied a large estate on Manursing Island.” The Times, along with many other reporters, headed to the Manursing estate, but servants refused to provide any details. Villagers proved a bit more loquacious, telling the Times reporter that Mr. Gould’s yacht was seen frequently at piers near Mrs. Sinclair’s house, “where it remained over weekends on many occasions during the past two years.”

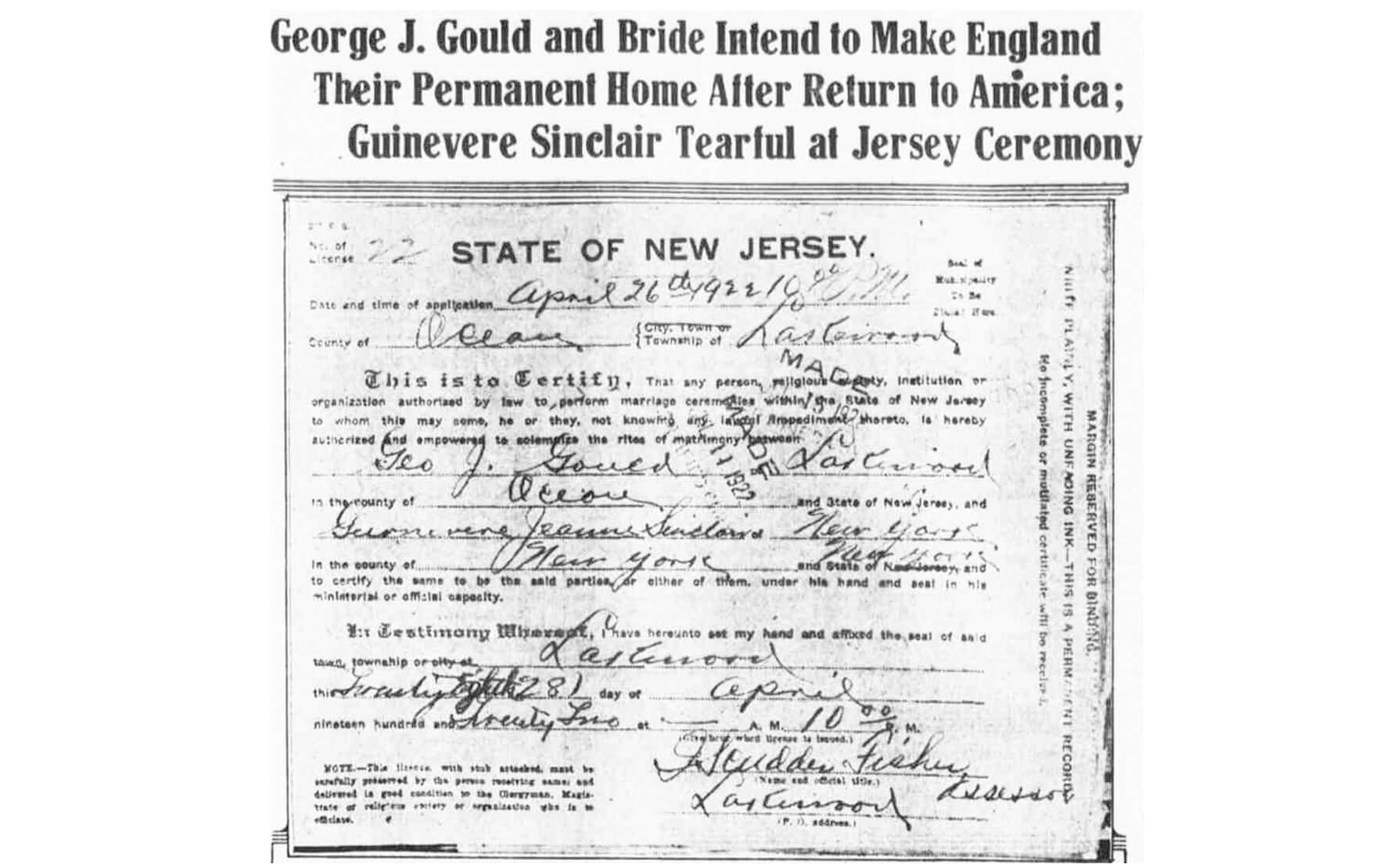

For multiple days the story was splashed across front pages as new details, confirmed and not, were breathlessly reported. The truth finally emerged when reporters discovered the judge who married the couple, not in Paris or London, but in New Jersey. The wedding took place on May 1, six months after the death of the first Mrs. Gould. The wedding certificate was printed on the front page of The Evening World on July 15, 1922, and accompanied by an extensive article digging into everything from what the bride wore to when the marriage certificate was filed. The certificate showed that Guinevere Jeanne Sinclair Gould was 29 years old, born in the U.S. and had a permanent residence on West 74th Street.

The newly married couple had managed to escape safely overseas before the full details were uncovered, but that escape took a bit of deception. Guinevere applied for a new passport under her married name on May 29, 1922, but identified three children — George age 6, Jane age 4 and 2 month-old Guinevere — as her stepchildren on the form. An accompanying typewritten note on Department of State Passport Agency letterhead explained that the applicant, Guinevere, had recently married Gould and wished “to keep the marriage secret until sailing.” The identifying witness on Guinevere’s passport application, lawyer Daniel M. Taylor, informed the agency that “the accompanying children are stepchildren of the applicant.”

Those three children were, it would eventually emerge, the children of George and Guinevere. George and Guinevere likely met in late 1913 or early 1914 when she was performing in New York under her stage name of Vere Sinclair with a Gaitey Theatre production of the musical comedy “The Girl on the Film.” It was likely Guinevere’s last theatrical performance, as she and Gould quickly became an item and he set her up in a house on the Upper West Side and then on Manursing Island. According to some of the writing on the Goulds, including Edward Palmyer Hoyt’s “The Goulds: A Social History,” the existence of the children was not quite the surprise for the extended Gould family as it was for the rest of the country.

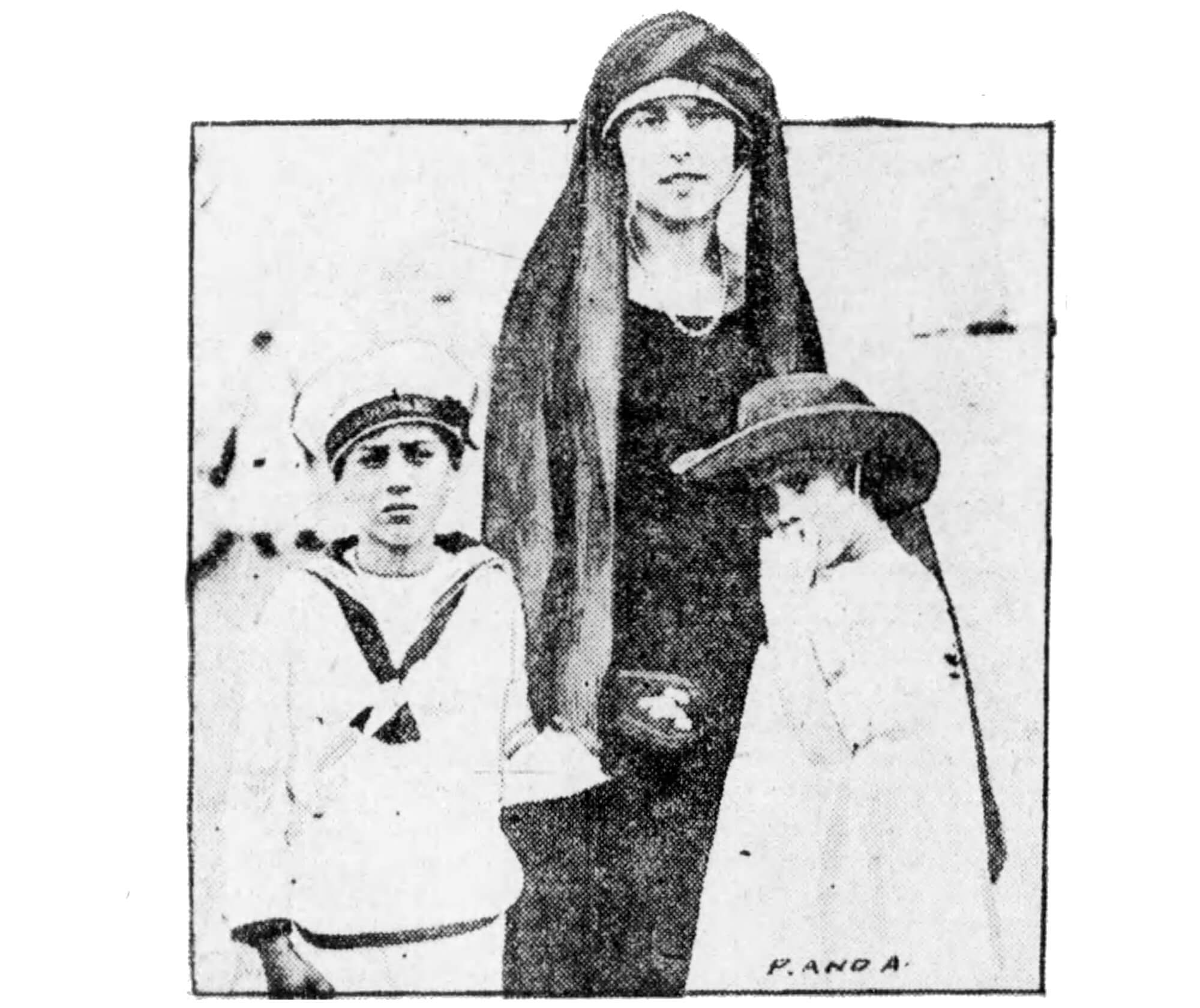

Papers continued to report on the story throughout the summer and fall of 1922, as dogged reporters tracked down photos of Guinevere, the children and her estate in Manursing. Guinevere’s estate was identified in some newspaper accounts as “the old Cromwell place.” Photos published in the newspaper accounts show that it is clearly 33 Island Drive, but the architect is unknown. It is possible that Gould bought the property in 1916 in Guinevere’s name and transformed it before ensconcing her and their children there a few years later.

Even the Brooklyn Daily Eagle got in on the action with a Brooklyn connection to the story in November 1922. The reporter chatted with sculptor Joseph M. Kratina in his studio on Prospect Place about a commission the artist had received two years before. He traveled to Manursing Island to sculpt marble busts of “Mrs. Alice Sinclair” and her children. The artist supplied the paper with photos of the artwork and used the opportunity to chat up the fine skills of his own son, a budding sculptor.

George and Guinevere stayed overseas while the gossip raged, but their legally married time together was short. Just a year after their wedding George died of pneumonia in France in May 1923. Guinevere traveled back to New York that June and the fight over Gould’s will commenced. The New York Times reported on the details of the millionaire’s will and according to the paper, “the most notable feature of the document” was that George acknowledged that he was the father of the three Sinclair-Gould children. While the battle over the will would drag on for years, it appears that Guinevere already owned the Manursing Island property outright.

Guinevere put her Manursing hide-away on the market that summer. The Catskill Mountain News reported that she planned to live abroad “and could not bear to rent the place” so it was to be sold. With a rumored price of $800,000, the estate included lawns stretching down to the Long Island sound, tennis courts and a golf course. Interest in the Gould saga was still strong enough that the paper reported that, with word out on the possible sale, a “watchman had to be stationed at the gate to keep out sightseers.”

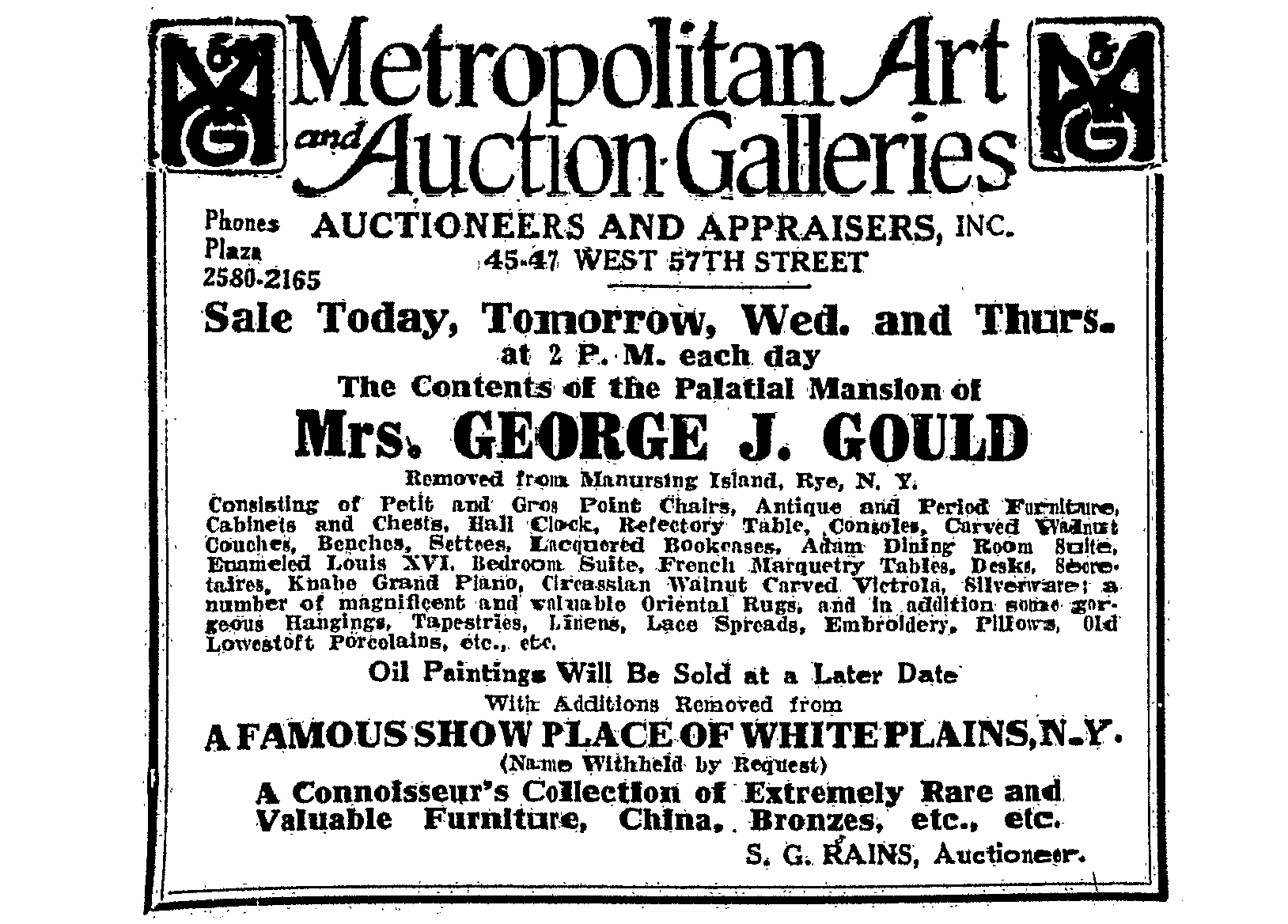

The curious could be kept out of the house but they had their chance to get a peak into Guinevere’s lifestyle when she put the contents of the house up for auction in October. The furnishings were exhibited at the Metropolitan Art and Auction Galleries for five days of public gazing before the multi-day auction. The first day of the auction brought crowds were so huge that “women stood on radiators and chairs in an effort to get a glimpse of the costly furniture, rugs and art objects,” reported to the Brooklyn Eagle. Mrs. Gould’s gilded chaise lounge brought “oohs” and “ahs” of appreciation and the paper calculated the first day of sales at $12,650.

The house itself sold quickly that same year for a price the Scarsdale Inquirer described as “a sacrifice” of $375,000 considering that Mrs. Gould “is said to have paid $600,000 for it” and had made many improvements. The buyer, interestingly enough, was J.H.R. Cromwell, a grandson of Charles Thorne Cromwell. The house was extensively documented by the Byron Company in a series of photographs taken in 1926. More than 30 images of the grounds and the exterior of the house can be viewed in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York. Alas, the photographs do not include any interior images.

As for Guinevere, her romantic life hit the papers again in 1925 when she married George St. John Broderick, Viscount Dunsford, soon after his divorce from his first wife, also a former actress. When he became the Earl of Midleton after his father’s death in 1942 the papers still hadn’t forgotten Guinevere, with one publication declaring, “Social triumph at last for scorned, long-suffering Widow Gould.”

Manursing Island has certainly seen some changes since Guinevere lived in seclusion in her grand Tudor-style manor. The once-secluded estate is now surrounded by other properties but the house itself looks remarkably similar to its exterior appearance in historic photos, with half-timbering, tall chimneys and oriel windows.

On the interior, the house has had some renovations over the years but there’s still plenty of period features intact.

The grand entry hall still retains an old English vibe with wainscoting, coffered ceiling, stained glass and a grand stair. If you don’t want to gracefully ascend the stair there’s an elevator accessible via the hall.

The vast first floor includes multiple spaces for grand entertaining. The parlor (now living room) has a working fireplace and doors opening up onto one of the two first floor terrace spaces.

There’s a traditional wood-rich library with doors to the same terrace as the parlor.

On the other end of the first floor is the formal dining room. While the listing doesn’t list the number of fireplaces, the photos and floorplans seem to indicate that there are at least six in the house.

As expected, the kitchen has been modernized since the 1920s, with white cabinetry, an island and a breakfast room.

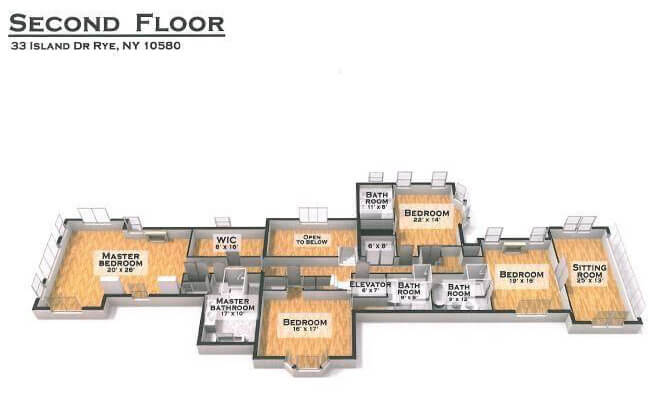

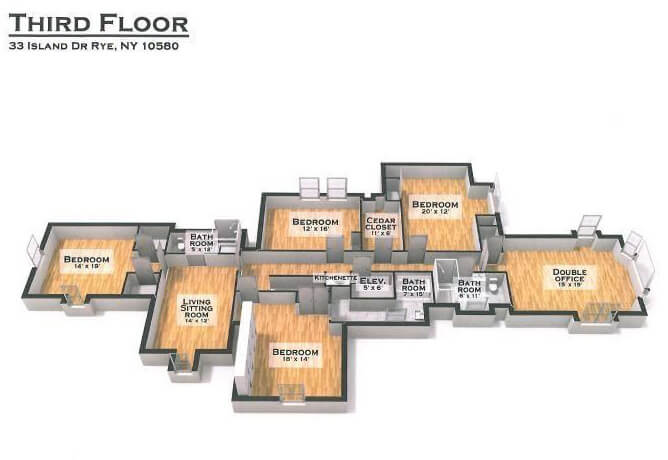

There are a total of 8 bedrooms in the house, evenly split between the second and third floors. There’s a master with en-suite bath and walk-in closet on the second floor. It’s also got plenty of windows and views to the water.

Some of the bedrooms include sitting rooms as well, making for ideal guest or au pair suites. The suite on the third floor also includes a kitchenette.

There are 7 full baths in the house on those bedroom floors and an additional half bath on each of the first and lower levels.

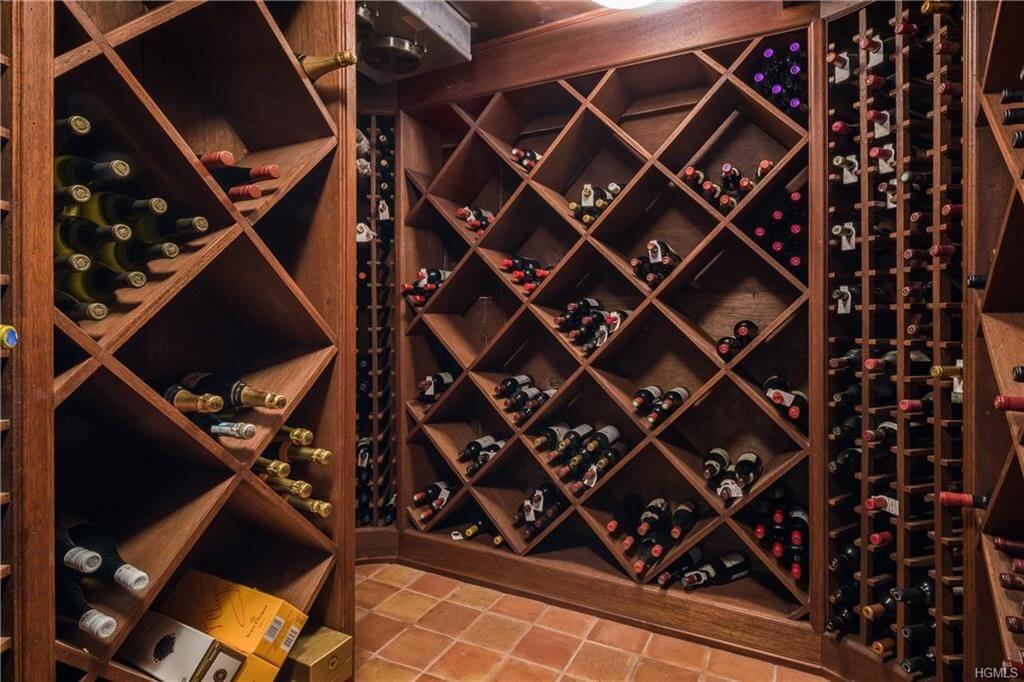

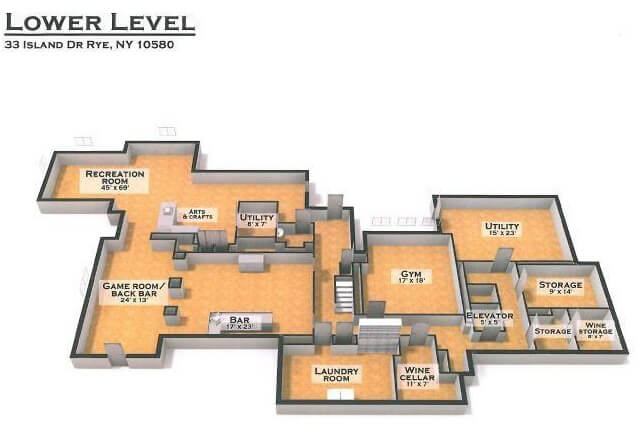

That lower level is decked out with amenities and entertainment spaces. There’s a game room, bar, arts and crafts station, gym, laundry room and wine cellar.

Outside the vast grounds that Guinevere and the children would have enjoyed have shrunk a bit, but there is still over an acre of land. Importantly that acre of land includes a pool and that water view.

You can snatch up Guinevere’s former estate for $7.795 million; it’s listed by Michele Flood of Coldwell Banker.

Related Stories

- The Poughkeepsie House That Pants Purchased, Yours for $530K

- An Irvington Gatehouse Escapes Demolition and Becomes the Home of Artist Charles Sheeler

- The A.J. Davis-Designed Country Retreat of a Former Pierrepont Brooklynite and Attorney General

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment