A Picturesque Pre-Civil War Manse by Architect Frederick Clarke Withers Could Be Yours for $749K

The Hudson Valley is a picturesque place, not only for its natural beauty but for the architectural treasures tucked into the hamlets and towns scattered on both sides of the river.

The Hudson Valley is a picturesque place, not only for its natural beauty but for the architectural treasures tucked into the hamlets and towns scattered on both sides of the river.

From cozy country cottages to grand villas, many of the rural residences were influenced by the work of a small group of architects and landscape designers whose designs shaped the look of the American home in the mid 19th century. With the publication of books of house plans that also included tips on construction and design, their work promoted picturesque styles with details like Gothic windows and Italian-inspired towers.

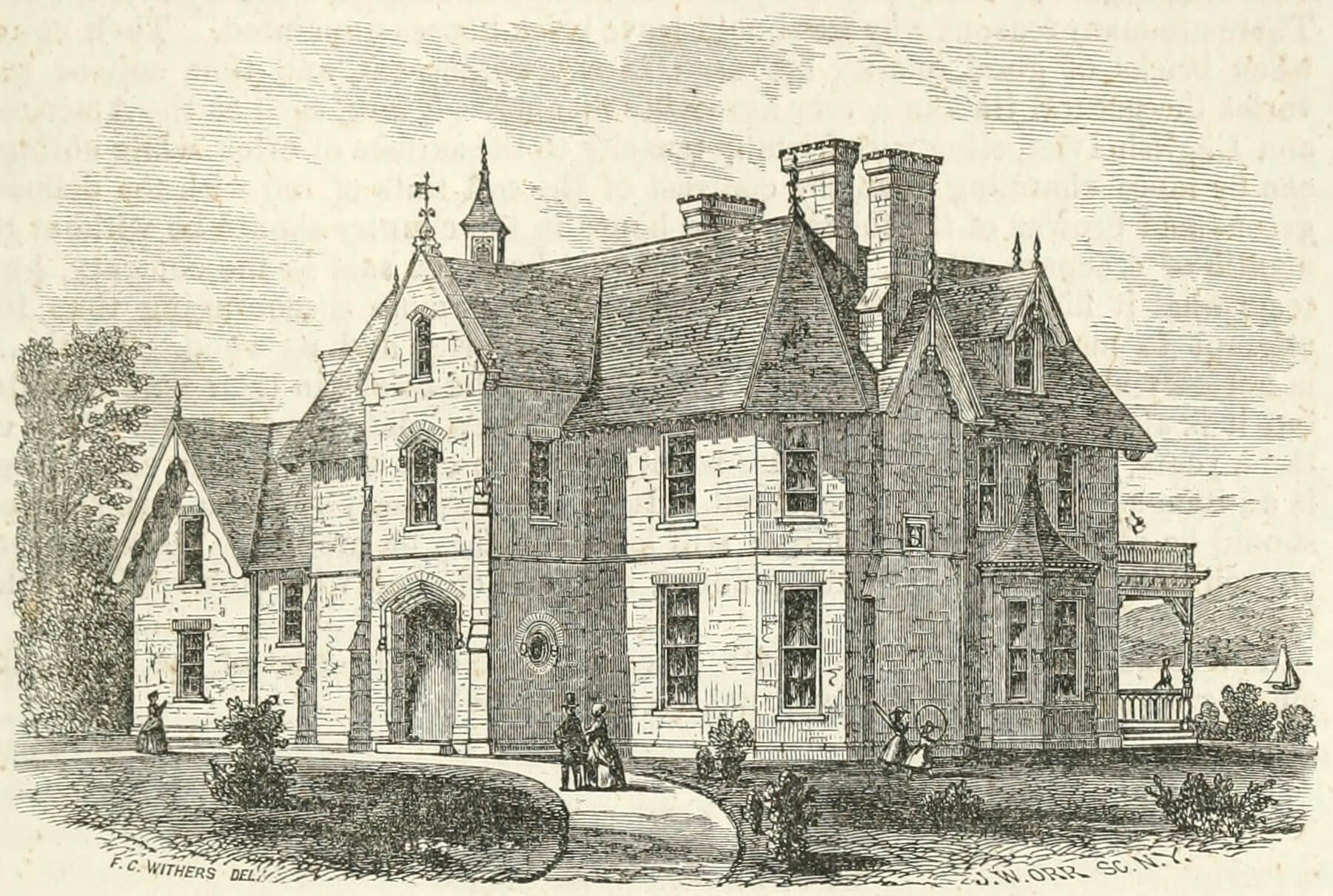

On a tree-lined street in Balmville, a hamlet adjoining the northern edge of Newburgh, is a house with a direct connection to these 19th century influencers. Glenbrook was designed by architect Frederick Clarke Withers circa 1856 for David M. and Pauline Clarkson and is a bit more of a grand villa than a modest country cottage. The house, located at 60 Balmville Road, is currently on the market.

Born and educated as an architect in England, Frederick Clarke Withers came to the U.S. around 1851 at the invitation of landscape designer and architect Alexander Jackson Downing. Withers arrived in Downing’s hometown of Newburgh, N.Y. and mixed with Downing and his colleagues like Alexander Jackson Davis and Calvert Vaux. Separately and in collaboration, they explored new forms for practical living and country home design.

Vaux, best known in Brooklyn for his work with Frederick Law Olmsted on Prospect Park, published Villas and Cottages in 1857, a compilation of house plans and suggestions on design and construction. The designs included some done in collaboration with Frederick Clarke Withers, who is also credited with the drawings.

While Glenbrook isn’t included in the publication, its massing is similar to the “Irregular Brick Villa” designed by Vaux and Withers and built for Nathan Reeve in Newburgh.

However, Glenbrook did make it to print that year. The house was published in the May 1857 issue of “The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste” and identified as a country house in Newburgh by Frederick C. Withers. The accompanying description notes the importance of the prominent entrance porch and the dark mortar used in the brick work.

Alas, the author would not be pleased with the currently painted brick as they specifically noted that “it is not only better, on the score of beauty, to leave the bricks in their natural state, but it is also more economical.” The cost for Glenbrook, including the roof, furnace and other finishings, was not to exceed $10,000, according to the publication.

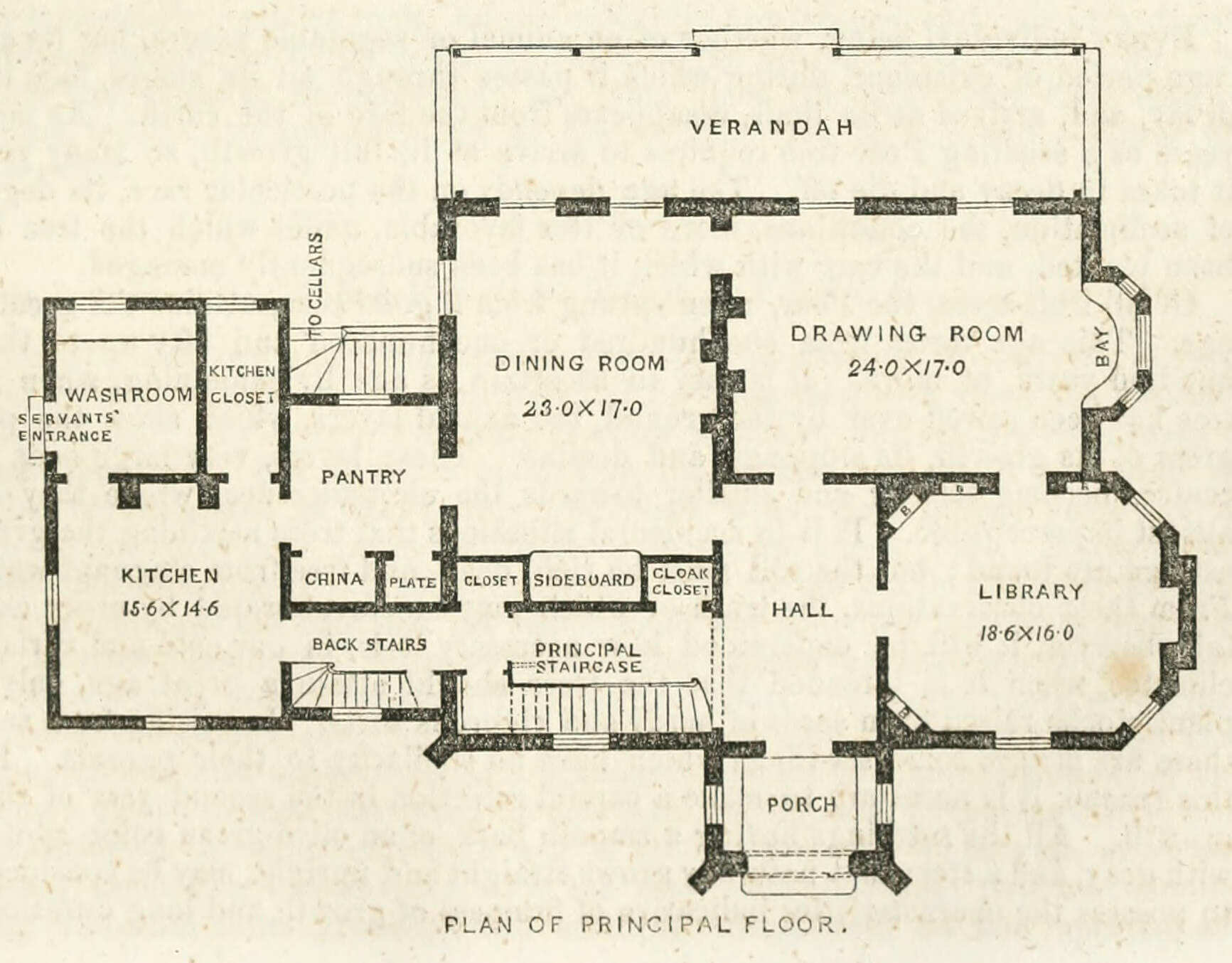

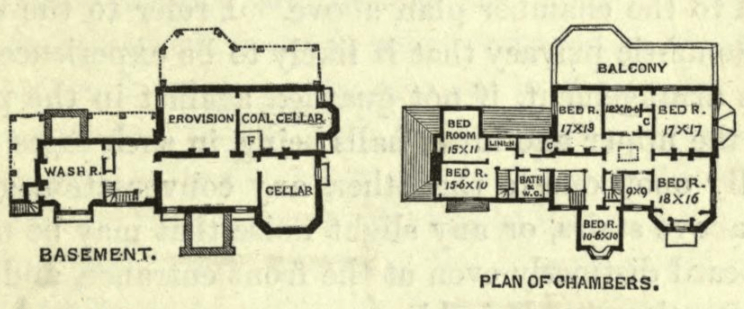

Only the plan for the first floor was included, but the write-up noted that the upper level included four bedrooms and a dressing room for the family, as well two bedrooms for servants and a bathroom conveniently located above the kitchen. The second floor plans of the Nathan Reeve house, published in Villas and Cottages, gives a similar layout.

It’s not clear what connection Withers may have had with the clients for whom Glenbrook was built. Owner David M. Clarkson was listed in the 1860 census as a horticulturalist, but the extent of his professional work isn’t clear. The year of that census David and Pauline Clarkson had a household that included their three young children, several Irish servants and a gardener.

By 1867 the family had grown to five children and, for reasons unknown, set out for Europe with a nurse in tow. Their sixth child was born in Heidelburg, Germany and it was there that Pauline died in late 1868. The brief mention of her death in the New York Herald in January 1869 described the family as “of Newburgh.” David eventually returned to Newburgh, but by 1879 he and his sons were settled on a ranch in Texas and he would stay there until his death in 1899.

While the Clarkson family may not have spent generations in Glenbrook, succeeding owners seem to have cared about the original vision for the interior as it is still fairly rich with period details. It was kept so intact that in the 1970s the Metropolitan Museum of Art used the library mantel as the inspiration for one in their Gothic library period room. The museum acquired the interior from the Frederick Deming house, another Withers design, in Newburgh when the fate of the house was uncertain. The mantel was missing so the one at Glenbrook was copied — which means that the buyer of Glenbrook could have bragging rights that The Met holds a copy behind a barrier and they can curl up in front of the original every night.

The listing pictures are, alas, not great. But by using them along with the original floorplan and description published in “The Horticulturalist,” it’s possible to see what details may have survived. In the entry, there are the grandly scaled doors off the porch. The entrance is situated so that it communicates directly with the principle rooms — a drawing room, library and dining room — so that they form “an elegant and convenient suite.”

The drawing room includes an ornate stone mantel, parquet floors with an inlay border and doors leading to the verandah for a picturesque view.

In the library is the original of that Met mantel reproduction along with built-in bookcases, a coffered ceiling and an elegant wood floor with octagonal inlay. The 1857 description says the floors were intended to be inlaid with oak and black walnut. It mentioned that the walls were to be paneled, which either didn’t happen or was removed at some point. The placement of the fireplace was carefully thought out so “that a person sitting by the fire may, at the same time, enjoy the lovely prospect which this room commands.”

There’s another coffered ceiling in the dining room and here there is rich wood paneling. The nook for a sideboard indicated on the floorplan survives and there’s another mantel and more doors out to the verandah.

The house was designed with a kitchen wing that included a back staircase for the servants, a separate entrance and pantry space. While the kitchen has clearly been updated since the 1850s, it is still located in that wing.

The listing says the property has four bedrooms, but the description actually mentions five — three with en-suite baths and two more bedrooms in the service wing. Many of those pictured have mantels, but the listing doesn’t specify if any of the fireplaces are in working order.

There’s also a third level whose five rooms are evidently not included in the bedroom count. Because of the dramatic sweep of the roofline and the dormer windows, the rooms pictured have a bit of a snug hideaway feel — or claustrophobia-inducing, depending on your viewpoint.

There are four full and one half bath and the vintage details of those pictured is a nice surprise. Well, at least for those who love a nice circa 1930s bath with built-in showers, cup holders and soap dishes and plenty of tile. If you don’t like pink there’s another in green and yellow and yet another in classic black and white.

The house sits on just under two acres of land and includes a two car garage. While it’s in the hamlet of Balville, it’s only a couple of miles to the center of Newburgh and its architectural marvels.

The house is listed for $749,000 by Jeffrey M. Lease of John J. Lease Realtors.

Related Stories

- A 19th Century Remnant of the Engineering Past Towers Over Weehawken

- A Wintry Tour of the 19th Century Houses of Newburgh (Photos)

- Can the Greek Revival Masterpiece of Newburgh Be Saved?

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment