Walkabout: By Justice Possessed, Part 2

(Photo: Library of Congress) The fiery preaching of Henry Ward Beecher brought him international renown, and assured that his Plymouth Church was packed to the rafters each Sunday. Beecher’s success was not just because of the eloquence of words that he spoke, but was because he believed so fervently in the causes he espoused. His…

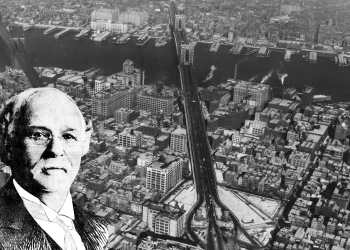

(Photo: Library of Congress)

The fiery preaching of Henry Ward Beecher brought him international renown, and assured that his Plymouth Church was packed to the rafters each Sunday. Beecher’s success was not just because of the eloquence of words that he spoke, but was because he believed so fervently in the causes he espoused. His was a muscular Christianity. It was not enough to simply talk or even pray, one must DO. And he practiced what he preached. His mock slave auctions and dramatic preaching against the evils of slavery raised huge amounts of money for Abolitionist causes. Plymouth Church was an important stop along the Underground Railroad, the secret highway for in escaping slaves making their perilous way to freedom in Canada. The influential and the famous made their own pilgrimage to Plymouth Church. Presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln attended a service at Plymouth before his famous Cooper Union speech. Walt Whitman, who shared Beecher’s hatred of slavery, also paid his respects. Mark Twain, on a speaking tour, attended a service, and would later write about Beecher’s theatrical and passionate preaching, saying that Beecher was sawing his arms in the air, howling sarcasms this way and that, discharging rockets of poetry and exploding mines of eloquence.

By 1854, the issue of slavery was dividing the country into slave state and free. That year, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which opened up those territories for settlement and statehood. Many legislators wanted the new states to come in either slave state or free, but the Act was vague. Organized groups of settlers, both pro and anti-slavery, swept into the territories and claimed land. Elections were held, and although only around 2,000 men were eligible to vote, over 6,000 votes were cast, most by pro-slavery factions from next door Missouri, who stuffed the ballot boxes for their candidates.

Although Kansas came in as a Free State, the result was a victory for slave holders, as sympathetic elected officials basically gave them carte blanche, setting off some of the worst violence outside of the Civil War. On the pro-slavery side, Quantrill’s Raiders swept through Kansas, killing hundreds and burning the town of Lawrence, Kansas. On the anti-slavery side, John Brown, his five sons, and their followers also took up arms and starting killing. Some of their weapons were paid for by Henry Ward Beecher’s direct funding. In 1856, Beecher was quoted in the New York Tribune, saying that the Sharps rifle was a truly moral agency, and that there was more moral power in one of those agencies, as far as the slaveholders in Kansas were concerned, than in a hundred Bibles. From that time onward, the Sharps rifle was known as Beecher’s Bible. It was illegal to ship arms to Kansas during this conflict, but shipments of rifles were labeled Bibles and books, and so made their way to Kansas, and to the hands of the anti-slavery factions. Today, buying guns for an armed conflict within the United States would be considered terrorism. Does a righteous cause excuse arming dangerous people? We still struggle with those questions today.

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Beecher and Plymouth Church raised enough money to support a volunteer regiment, and Henry Beecher travelled to England and around the United States, raising funds for, and championing the Union cause. He would often be a thorn in President Lincoln’s side, as he was quoted as saying he was unimpressed by the activities of Lincoln’s cabinet, and wondered about the president’s intellectual capacity. He would on other occasions then praise the President and his actions. Beecher biographers have written that this was classic Beecher. No one was really good enough, or their actions sufficient to please him, and he often had acrimonious relationships with some of his strongest allies. He himself is quoted as remarking about letters written to Lincoln, “I wrote a series of editorials addressed to the President (three or four), and as near as I can recollect they were in the nature of a mowing machine — they cut at every revolution. Beecher would let up on Lincoln only when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

The Civil War ended in 1865. Beecher would preach that the Southern leaders deserved places in the depths of hell, but he eventually urged reconciliation for the good of the entire nation. Like any victorious general after the war is won, Henry Ward Beecher was now without the major driving point of his life. So much had gone into his hatred of slavery, and his efforts towards ridding the nation of that legal imprisonment and forced labor by an entire race of people. He must have been both elated and drained. Fortunately, there were still lots of grand causes to champion. The mixture of the pulpit with politics never bothered him. He was an ardent supporter of the new Republican Party, which had been born in the furor over the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. He supported opening up the US to full immigration from China, not just the temporary immigration of a male labor pool. He was an enemy of gambling and alchohol. He championed women’s rights and equal rights for all. He was the reformer’s reformer. He gave a lecture at Amherst, his alma mater, in 1871, where he stated, Amherst is for universal education. If a man be black, and is fully prepared, or a woman, and is fully qualified, its doors will be open to them. Amherst should lead in this march of progress. He also believed in the concept of free love. How he chose to exercise that concept would get him in a lot of trouble.

People love you when you’re famous, and love even more to watch the famous fall. His infamous and scandalous affair, the trial, and the end of the story – next time.

BSM- isn’t Harriet rather lipless? Jodie Foster, Holly Hunter, (and again) Patti Smith. If they do it as a musical, I say Madonna.

Absolutly not Brad Pitt. I an still voting for Russell Crowe. Winona Ryder as Harriot.

Nathan Lane & Christine Baransky.

Philip Seymour Hoffman. Hands down.

I see it more as an indie movie, Minard. Less commercial choices- Robert Mitchum would have been great, or Burt Lancaster.Jodie foster for Harriet?

If it is a Hollywood movie it will be Brad Pitt playing the role of hunky reverend and Angelina Jolie as Pinky. Natalie Portman could play Harriet Beecher Stowe.

I am voting for Russell Crowe who I think can handle the role. However, unlike most women I do not find him sexy or very attractive.

Too gorgeous and doesn’t look crazy enough 😉

You need someone who gets all wild-eyed and Mr. Hydeish in his most inspired moments

Can’t wait for the next installment. Great job MM